Swafield and Bradfield

‘Fruit picking’ and ‘Pick your own’, are something commonly seen on hand painted signs still wedged in hedges and gateways across rural East Anglia and the Fens, it was and is part of a year long routine in Norfolk, especially with summer fruits. A memory flickers up from somewhere as I drive, I’m here and not, between sunlight and cloud on dusty farm tracks and the straw-floored strawberry rows of the 1970s. We all went with mums, a few dads maybe, in groups, helping them. We mucked about eating strawberries, lipsticked our mouths, threw mouldy fruit at kids from the other school, engaged in mock war or had standoffs with the Romani and traveller kids. Ignored the glowering farm-hands and the irritated calls from parents. Mothers worked, squatting down or kneeling on old jumpers, rugs and towels, backs curved against the wind or sun, headscarves on, necks reddening. They worked up the rows leaving the unripe fruit for another day, chatting as they went. It was housekeeping or extending the often low-wages you tend to find in these rural areas. For us unfocussed children, it provided a small amount of pocket money if we ever got cajoled enough into doing any picking.

As we got older we’d head out ourselves in groups on bikes, fill the card punnets, then pick up the vendage doled out beside a trailer by an old man with a backwards cocked flat-cap. He’d fill crates and then a shirtless lad with berry coloured shoulders hefted them onto the high pile on a trailer. It was part of life; strawberries, raspberries, red and black currants, later in the season carrot topping by hand, onion picking near Sutton. Gooseberries were the devils work; no gloves and you’d end up filling buckets with them from wounded hands; stigmata for cash. They were all weighed off and money doled out all over the swathe of the fields around the north of town. In the teenage hinterland, it was enough to buy Airfix kits, comics, records or crafty brews from the off-sales section of the Lord Nelson. The bottles were topped on the brick wall in the precinct, we’d think we were dandy. Then drink, savouring the foretaste of an imagined future freedom buried in the skinhead-free shadows below the outline of the busted church.

The route up and out of North Walsham is eerie in its familiarity. Despite the distance in time, and the bypass sneaking away from the old familiar line of the Mundesley Road, it is still a route full of echoes. Fruit picking aside there were beach trips, rides to chip shops on the sea wall watching the ships lights like glowing beads on the seam between the sea and sky. Teenage bike rides to pubs where landlords seemed grateful for a customer no matter how old they were, and gigs in dingy village halls through cheap crackly PAs, It feels strangely like it’s still home, a dusty and broken Scalextrix groove worn into my memory around these weedy roads and paths.

Familiarity doesn’t mean I won’t get lost, thinking I’m being clever I explore the thin side roads for old times sake. I lose myself twice as I circle through the area between Bradfield and Swafield, end up in the distant urban headiness of Southrepps for a moment, then resort to Googlemaps. Between the high hedges, even the tallest towers rooted in the slowly cresting and breaking rolls of the glacial tills are lost behind the summer growth. It seems like there’s more trees, everything more profuse from a lower vantage point, a driver’s perspective rather than a rider. The lanes are a cars’ width, divided in half by grasses, even a few flowers slash at the sump of the car.

It feels strangely like travelling backwards in the quiet lanes, buried in this bocage of hedges and tunnels of trees. It is unremittingly quiet and beautifully still. I pull up occasionally where there’s room in field gate. It’s not all fruit-growing here, where the banks lower the patched vista opens up, the wheat stretching off to the horizon yellowing with the passage into July. From above it is a pattern of ripening cereals and glossy swathes of beets greens, interspersed with the paler leaves of the fruit.

I only see three people; an old boy, sweating hard as he slowly cranks his bike up a rise, I pull in to let him pass, he beams at me and slowly raises his hand in a gesture of thanks. Then from a path near the old round pillboxes; remnants of the Great War stop lines; two girls appear, the younger one, astride a bay horse the other leading with a halter. There are no other cars at all, just me, slightly lost, pretending I’m not, not minding, nothing is far away.

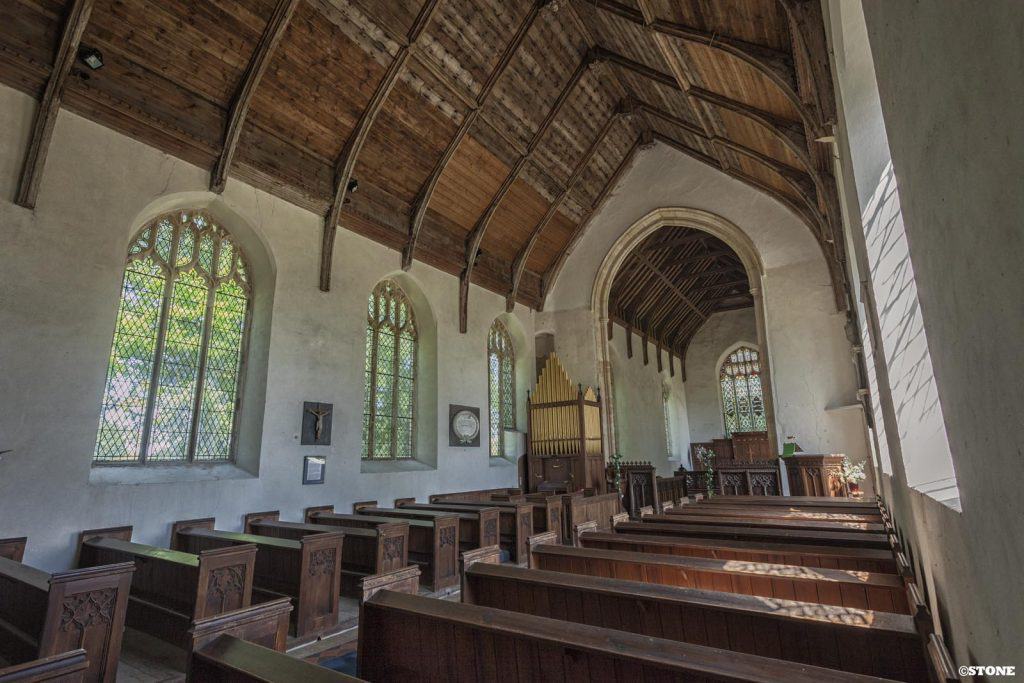

St Nicholas Church, Swafield is above the village on the rise towards Trunch, the road is vaguely busy, a car every three minutes plying up the low ridge toward Trunch and Trimingham; for some unspecified reason they’ve shut the B1145 and diverted its boastful two-way traffic up past the old church. I doubt many people notice the building, these places become part of the furniture Norfolk’s agrarian landscapes, and little St Nicks is enveloped in a sleeve of trees set back far enough from the road to allow for parking a small congregation along the front.

The building is neat, compact and nestles down nicely in a sea of mixed growth. The grass trimmed in places and left wild around the older graves. The building is apparently late medieval according to Knott and Pevesner, my limited knowledge of church architecture nods dimly in agreement. There is talk of it being a rebuild, clues in the walls. What was here before the money of wool and weaving is largely a mystery. It’s this money that built and rebuilt. In most cases they replaced something smaller, sometimes wooden, occasionally materials can be seen, bricks or tiles robbed from elsewhere that hint at previous lives and cultures. One thing I do know is that from our vantage point now, in the digital era, this place flows back some time, not so much the building, but the inhabited living landscape around it, still marked with traces of that ebb and flow of life, worship, industry and agriculture, you cannot erase the past, it hides in the weeds and crops.

The catch is stiff and loud, the inside quiet. Time temporarily breaks into pieces, suspends itself, hangs motionless in chunks. The church is well used, there are second hand books piled up for sale, leaflets about the diocese, a visitors book; I’m the first today to mark an interest; I came here to see one thing really but as usual I’m surprised by everything, perfectly distracted from my modern life by the faded receipts of others time here. There’s no wall paintings, it’s plain and whitewashed, fresh but flaking and cracking in places. Large perpendicular windows flood the body of the small nave and chancel with light, there’s pools coloured by some nice Victorian memorial glass. A mother paid the world in glorious colour to remember her sons from Swafield Hall. They are the Dolphin brothers; Henry, a Boer War casualty died in 1881 at Laings Nek, Edgar drowned at the other bookend of what must have been a despicable decade for their parents. The window features St Cecilia, patron of musicians, and St Nicholas patron of sailors and choirboys. They flank Christ the shepherd, all of them lit by bright summer sunlight on this faintly sloping hillside nearly 130 years later. Those lads still here singing a few miles from the sea.

The font is workmanlike, quatrefoiled. A niche contains a plaque commemorating the parish’s war dead. I count 10, 4 from the first modern war, 6 from the second; Bayes, Childs, Peek, Richmond, Agar and Agar, Clabburn, Renacre, Starling and Sexton. One of the farms here was owned by a Starling, I knew one of the sons. It’s a fair number for a small farming parish, doubtless felt and acknowledged here still with poppies.

The roof is curious, the curve of it almost boat-like. High up in the apex 8 bosses are fixed, they are quite strange, they don’t feel like they fit here, almost theatrical, tudor fairground horror, quite malevolent. There’s something distinctly weird about their mocking glower. There’s a striking lecturn, an art nouveau piece, the features rather beautifully found in the wood grain. A curious crucifix retrieved in 1937 in pieces after a storm from the beach between Walcott and Happisburgh is attached to the plasterwork above a framed inscription which warrants a reading, it contains the names Mileham and Sharman, both names built in the Norfolk sand and clay along the curve of the coast.

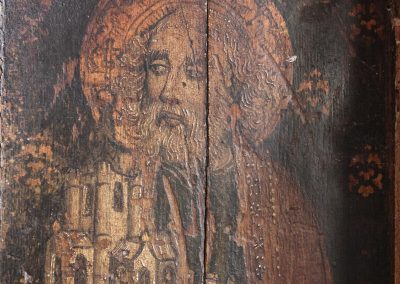

The prize is the rood screen. It is apparently contemporary with the church with some repainting, probably Victorian, I can’t tell, I’m not an expert I read about it. I know enough to stare at a face and feel it’s gaze fall back through layers of dirt, cuts and varnish onto me. And these really are quite haunting objects. St Peter in particular slightly blows me away. The fragility of the surface open to the air, years of people’s breath and dust ground in, the cracked and pitted panels, blistering and peeling, parts scratched away by puritanical outrage. If they were animate what would they have seen, I wonder with paintings like these how much the painter extracted from real life, where these depictions of saints and angels based on people the artist knew? Imagine that, anonymously and unwittingly still staring out into the world trapped behind a remorseless, thickening veil of dirt for 700 years, watching the generations come, grow and be replaced; plague, love, war, marriage, death, birth, over and over.

There are eight of them in total, 4 pairs. On the left Andrew and his saltire, almost more wood than paint. Then my favourite, a Pre-Raphaelite Peter carrying the heavenly city and keys the weight of time passing cracking his panel, his beard, raised paint. Next Simon and his fishing boat both zealously scratched at. Jude and pet fish, a stripe of white bird shit running down his face. On the right; James with pilgrim staff and purse, his face crossed through, the marks of strikes with a hammer or pole cutting pennies into the wood. St John is a cartoon, chalice in hand and a spiders nest in between his pursed lips. St Thomas with spear, guilty as sin, and finally St James the Less and his club, lips pursed, a light patch on his hands where Pauline Plummer tried a cleaning test. The reds are solid ground out of earth, the gold leaf still glitters where the coating is thin. They are worth the trip back to the fruit fields, the strawberries and the gooseberries.

Outside I wander around the graves and read a few, Walter Pardon is here, the folk singer, his gravestone dwarfs the others, his quiet life carrying on the songlines of Norfolk ending here near the tide of tall grass, next to him I recognise what I think is a Czech surname, there’s a Scot, mixed up with locals. The finishing line moves forward. Through the trees, nearby in a field the flow of time reverses. An old village sleeps under the soil, the continuation of movement and human history here is strong. Swafield now below us on the corner creeping slowly along corner of the B1145 isn’t the original Suafelda. That is almost certainly near here in this open land, where the tracks still mark the summer crops as they grow unevenly over old banks, ditches and housing platforms drawing moisture up from these buried features of these lost swathes and tracks. You can almost hear the Anglo-Saxon remains of the words in the name if you say it over and over again.

The earth is deep here too below the village, a buried farm that predates it by at least a thousand years. 8 times the size of the church and cemetery, A double ditched Iron-age enclosure is hiding below the medieval village. These feet-drawn patterns criss-cross below the waving ears of the crop, below the vapour trails of our travel, the medieval didn’t obliterate it, nor has the plough, and the eyes still stare up and out.

Possessed of nothing more than Hell

Before I can speak

My world is wishing me asleep

And when the darkness comes around

Repeating heads

Remember nothing I have said

Come back again I want you to

‘Not now girl’ you say

But I was born to lose my breath

Lyrical. St Peter is a treasure.

The top photograph is so beautiful.

Thank you Zoe.