Stratton Strawless

There is this thing were you travel through a landscape, passing things, that have become lost, part of the blur of the countryside, the unnoticed facets of a landscape which sit just back, away from our arterial routes cut as they are by human traffic. It’ is also easy to forget that these thick laces of tarmac radiating out from the nuclei of our cities and towns were originally desire lines made by feet, and animals, then etched harder into the soil by carts which became cars and lorries. These thin sinews started as a dirt tracks, widened by herders heading to markets, plied by the trade from the coast or the county supplying rabbits or vegetables, lumber or wool. Now capped by tarmac to withstand our haste and weight.

We all idle along these grey threads glancing out from behind slow haulage trundling along at 50 miles per forever on our transitory paths to the chip shops and amusement havens of what were the old fishing villages and ports. Or heading of to drag a dog or bicycle from tree to tree only to end up in a less than stately tea room surrounded by the remnants of collapsed lordly splendour. Those not-really-our-pasts; frozen somewhere before the mid-twentieth century when the money dried up for lots of the descendants of robber barons and flock-masters in these big sheep farms and their country houses.

It’s all part of our blink and you’ll miss it culture, place-names are a tiny blipvert of our collective past hidden in between the tracks and tree-lines across the county and the country. It’s here a simple turn off the artery and onto the capillary networks of grass-split side roads and blind corners where only residents venture that the stories are often revealed – what grows, what fruits, and what dies. You forget in those glances away from the grey veins, that the road signs flicking by mean something, more than just a direction.

Norfolk has a wealthy past for certain sections of society: we were more important once than we are now. Wool specifically brought riches for some, and as the quartered seasons rolled past and times and farming changed it was those people who sent most of us tumbling towards the city. Many of our forebears were forced out of the countryside either by the shift away from cereals, beets and beans to sheep, and many of the remainder by the mechanisation of arable farming. They would have adopted new trades that didn’t involve the land directly, instead the processing of its new crops; wool to cloth, skin to leather; the flow from these industries built big fine houses on large tracts of land once worked by ‘us’ – the crumbs and drops of which watered us, usually at subsistence levels in the cities – working looms, weaving, dying skeins. The loss of the marl under us meant a different dirt coloured our skin, The dirt and back-curving harshness of working the land swapped for the toil of dyeing, weaving and tanning.

In some places the soils are poor, a blasted heath – Wroxham crag with it’s belts of sand and gravel provide a sour footing for traditional arable farmers to eke out an existence, easier and economically more sensible to plant bands of trees or have animals graze. There’s more than a possibility that this is what we can see here remembered in the old English addition to the name Stratton Strawless; ‘strēaw lēas’. It was barren to our food grasses; bad for grains, bad for planting, better for woodland.

And Stratton Strawless theoretically as names go casts the net further back. Strat~ is a paved way, a street, a common word absorbed from the Latin ‘Strata’ into the Germanic tongues of Northern Europe. It is or was a town or settlement on a street and it may well be indicative of a Roman road that pre-existed the later migrants from the east; the Angles, Friesians, Saxons and Jutes used it as descriptive of something already there, often Roman, so they wandered here too, shifting their produce and fish about on these same trackways and roads.

Once you get off the main road you vanish into the stands of trees, If you look at the world refracted through Googlemaps here you can see the waves of them breaking along the faint ridges to the north east of Norwich which mark boundaries or cracks in the tide of ice that flowed over the county. Not far away to the west, just on the other side of the A140 in Horsford Heath these same bands of trees hide the silent remains of the Bronze Age, still sleeping in barrows flattened into the bracken and heather beneath seemingly silent pine stands.

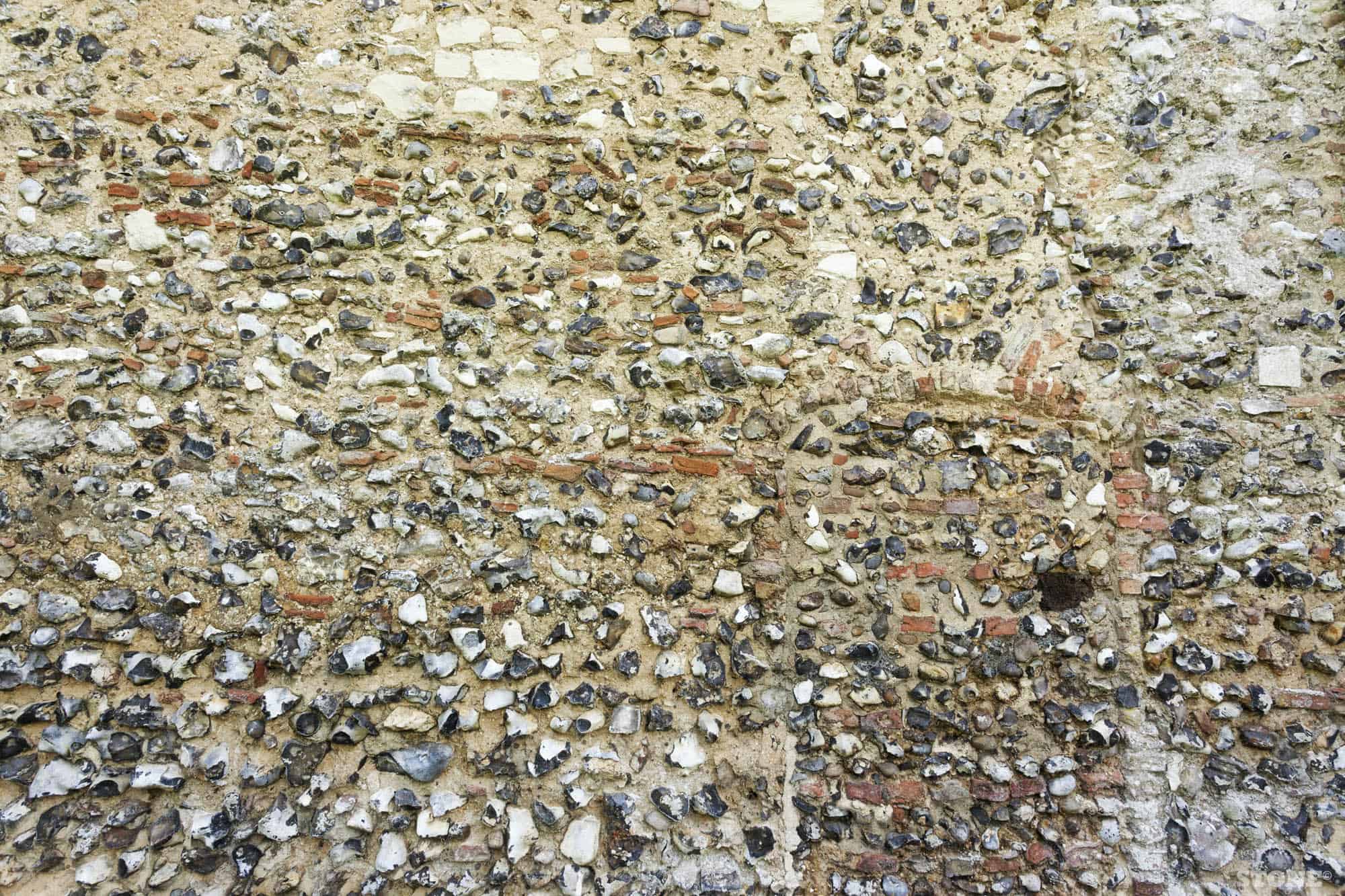

Stratton Strawless sits between the A140 and the Buxton Road which runs more south. This may be the street in the name – equally it might not be. Evidentially there is little to go on, but it’s believed to run from Burgh and Brampton to Thorpe St Andrew. The village sits on dog leg in a reasonably straight road that runs from Buxton to the A140 sliced through to form a crossroads of sorts that peters out into track-ways to the north, and splinters off into Hainford and Newton St Faith in the south. The church and village huddle around that kink. The Romans have left a mark here, indistinct, but visible; fragments of Roman tile and brick rub shoulders with freestone inclusions and flint, all sitting together in the layers of the walls of the church. The concentration of reused material appears most heavily on the outside of the fourteenth century chancel. Someone somewhen, either knocked something down or dug something up and put them here, feeding our past into their present.

Stratton Strawless was the province of the Marsham family for over 400 years. It doesn’t take more than a glance into the puddled light and shadow of the Church of St Margaret to realise how important they were and equally how important they believed they were. There’s a huge amount of stairway to heaven purchasing going on inside. It’s not a huge building, squat with a low rebuilt tower. Tombs built for lesser later Marshams huddle around outside the south door, the poorer locals line up in rows spreading off into the shade of the trees. It’s certainly pretty, a nice setting, the old rectory over the road, the trees, sunlit flies and the candy floss of thistledown drifting about in the late summer light.

St Margaret’s is probably of late Saxon origin but what is visible is largely Norman and medieval with a fair bit of interesting gothic Victorian meddling in evidence. The inside has been curiously carved up with screens. The south aisle accommodates the Marshams in some fairly outlandish tombs – a mausoleum for them of a size and type suitable for a family which featured mayors, MPs, lords and gentry. Large imposing almost ugly things carved fro alabaster and marble, with flecks of gold leaf. This is their chapel, they inhabit it now with a large library of paperbacks, jostling for your attention with assorted Clive Cussler-alikes, hard-backed slow-cooker and freezer recipe books from the 1970s, dog-eared Zola and Camus, and the ubiquity of the crime novel.

The larger memorial on the south wall is shared; Henry and Ann Marsham and their children. It dates from the late Seventeenth Century. Ann died in childbirth in 1668 and is buried with her stillborn child. Henry dying in 1678. They kneel supplicant, palms pressed together, Henry and Anne flanking Henry their son who died aged 12. To the side of Ann is Margaret who died aged less than a year, swaddled forever in alabaster. It is sobering read, this stone thing.

The other memorial is more surprising in tone. Thomas Marsham who died in 1638 sits in a triumph of comfortable death, reclining on a cushion in a roman pose wearing his shroud. He looks rather effeminate and curiously his face is unshaven, which may or may not have been to counter the feminisation of his robes. Gilded angels with trumpets hover above summoning us all for our resurrection which must surely come, and he’ll be ready for it once he’s had a shave. Below, perhaps most fascinating, is a charnel cage. If I’d not known better I’d have assumed the skulls and skeletal fingers reaching out were real.

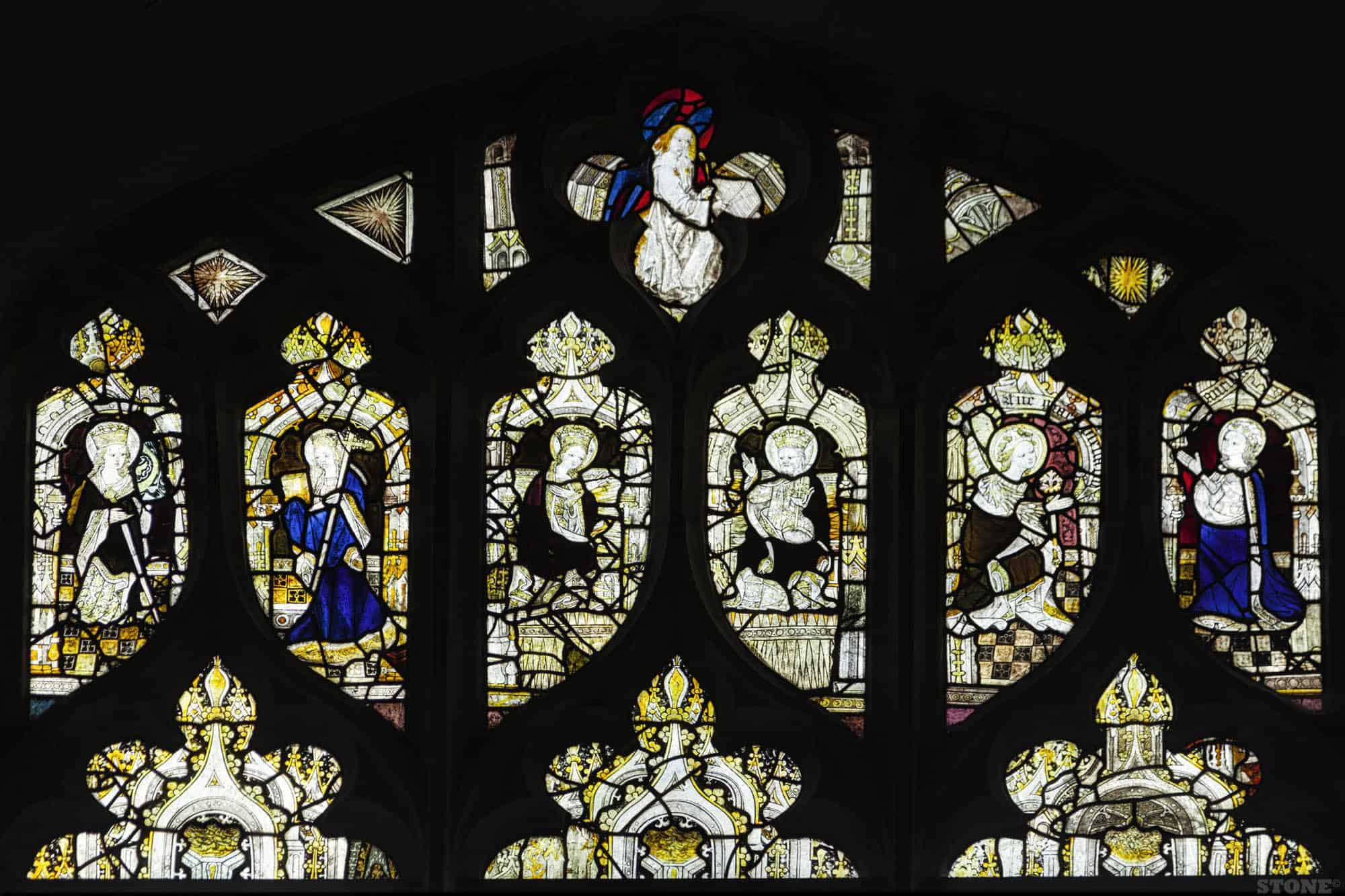

Along the nave there’s a huge Russian chandelier, some rather beautiful medieval glass twinkles down from far above, it’s important stuff, but I don’t have the required lens for catching it how it deserves. In the corner on the north side lies the Black Abbess, a misnomer in all probability, but an intriguing one. She was found in the tower during some renovation work in the nineteenth century. It’s a simple black memorial, a woman laying down holding a rudimentary heart in her left hand. She is alleged to be the wife of a crusader, now both nameless. The heart? her husband lost abroad.

It is perhaps apt that this has taken me since late summer to finish writing this, given that spring is now edging towards us while the chill and damp of winter still extends icy finger through it’s cage at us every other day. But the signs are there, snowdrops first flowering on Instagram… And there is a reason we record these changes, the cycle of the seasons warming our skin or chilling our bones; those first snowdrops, the call of the cuckoo, swifts, swallows and martins returning to our skies, mating calls, plants leafing and flowering, insects suddenly appearing and drifting by in the seemingly endless cycle of the seasons through the years.

It was Robert Marsham’s fascination with trees that first flagged up recording these signs as worthwhile and Phenology was born. I stood in front of a display in the church, a collection of panels and roller stood there laying out his achievements. Thomas was born in January 1708, a naturalist he was obsessed by recording in detail the signs of spring. Effectively the founding father of studying climatic variation something he continued for most of his 89 years, his family carried on his habits well into the twentieth century. It is a form of data collecting we still use, and the increasing earliness of spring is one of the many ways we can see climate change and global warming in action. Somehow almost unknown to most, including me until I stumbled upon him in the church, he towers over Norfolk and our future as a species, like the over one hundred foot high Cedar in the woodland he planted as an eighteen inch sapling in 1747. Most of his planting was felled during the First World War such was the need for timber for trench revetments, sleepers and limbers, but this one remains, its head well above the beech and oak that surround it and is visible for miles.

The Marsham’s 14th century grand seat at Stratton Strawless Hall is not far away, not the original house which burnt down, this is clean cut nineteenth century construction, perhaps overwhelmed by the richly designed and planted parklands around it which thanks to Robert were pre-eminent. This one also has the distinction often seen in Norfolk of being a base for the RAF during the war – part of their radar network. The land has since I suppose returned to us. Now flats and caravan park, I knew someone who parked themselves here for a few years in a static caravan at a loss as to how to afford a house in the city on county wages. So there we are, pushed back out into the countryside, people rooted where where the straw won’t grow.

Albatross

Subtight turned on a dime

In the sultry west-coast night

How could you lost your roll

Amongst the hopeful and the drunk

You showed me so much

You showed me so much

Took us to the new house, speeding along

In a green machine

Riding the wake of another

Once a week

You showed me so much

Oh you showed me so much

Those days are now long gone

Wish I had your picture

Never been able to be true

So I wanted, I wanted

I wanted to help you

I wanted to

And I wanted to help you

And I have to admit

Things got weird for a bit

And I scream for you

There goes my man

And I scream for you

There goes my man

And I scream for you

There goes my man

Peter Green/Besnard Lakes