I’m a virtual veteran of two world wars, one in particular; The Great War, the one to end all thingummys… as an anomalous title for a war as there could possibly be. That aside I do a lot of, or as much as I can afford and fit into life without annoying my very patient family, stumbling about in muddy fields where the First World War or Great War happened. It’s a long story that relates to my upbringing and my family and how I remember that and how important some bits of my family have become, disproportionally so in a lot of ways. So, I have Trench Fever. I’ve just returned from a soujourn with my vast muddy therapist in Belgium; The Ypres Salient. I’ve done this trip a few times, this time I decided in a somewhat disorganised way to cover the lower half of the salient rather than the top bit or the middle bit that is so important in my heart and my head. I didn’t intend to write about the bit I’m about to write about particularly either, but something caught my attention and got me wondering and wandering and I ended up on a promise to record it here because it seems quite important in the oncoming debate as the centenary approaches that the debate has more than one side, because a debate with one side is a boring monologue about what it all means, and I think we’ve already had one of those from Mr Cameron who says much but knows little on the matter So we need a dialogue, a co-operative and reflective look at what happened and what it means rather than some flag waving. I’m about as keen on that sort of thing as Wilfred Owen was. I’ll explain The Salient in more detail another time, an probably explain my relationship with it in elaborate yawning detail, but we’ll start with this at “Plug Street” as Tommy was want to call it in that stereotypical, “I can’t talk foreign way”.

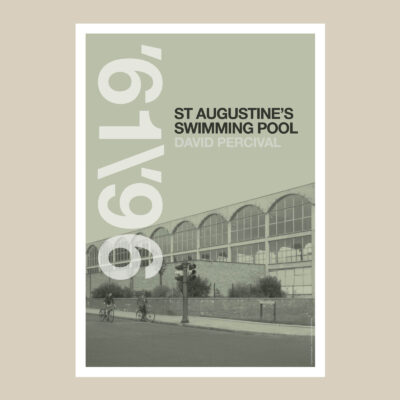

I’d made up my mind to give Ploegsteert Wood a quick visit, mainly to shoot the iconic ionic memorial at Hyde Park Corner, it’s very much the Greco-Roman rotunda with it’s two lions guarding it, one angry, the other a bit glum. The memorial lists the names of 11,367 men who fought here from 1914 onwards, major actions at Armentieres, Aubers Ridge, Loos, Fromelles, Estaires, Hazebrouck, Scherpenberg and Outtersteene Ridge, it also represents the fact that men lived here, cooked, ate, slept, scratched and yawned, and ultimately died here from those small everyday instances where death appears, being too tall, standing up at the wrong moment, cutting yourself and getting septicemia, falling in a hole full of gas, randomly catching a bit of shrapnel somewhere soft, that type of thing. The memorial was supposed to be erected in Armentieres, but ended up probably in a better place representing the Southern sector as it does. It was designed by Harold Chalton Bradshaw, and the Lions are by Gilbert Ledward. We found the memorial at 11.30 in the morning, we’d got a bit lost round Kemmelberg before that, Kemmel is beautiful and sad, but that is another story. We had a saunter about, looked at the memorial as you do, I did all my photographic things that I like doing and tried to read a QR code on the CWGC signs that didn’t work, got laughed at for rabbiting on about stuff and pointing at things, then we turned to head back to the car and I spotted something vaguely unusual, this happens. You get ‘other graves’ in CWGC plots, odd French graves with there funny stone, and German ones, this one caught my attention more than usual for some reason, so I snapped it, figuring as it was legible I could look it up and try and find out about this young chap buried in the corner of a foreign foreign field. Here is the photograph of said young chap, lying amidst his comrades in arms and filth and sweat and rubbish food and lack of sleep and lice and so on. So here is; Leutnant Max Seller sitting at the end of a row, he also has three other German comrades in here I’ve since found out.

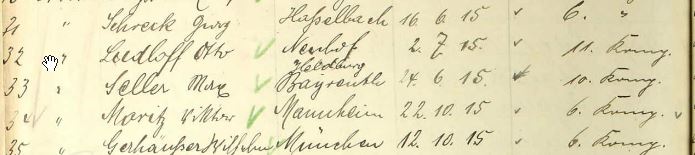

It’s a curious grave marker, the squared corners, and German memorial typeface, but appears to be the Commonwealth War Graves Portland stone, presumably the black teutonic markers would have been a bit jarring in this context. When we got back to the hotel that night, I spent half an hour seeing what I could find online about him or German WW1 Archives, or in fact anything. I’ve done plenty of research for ‘Tommy’ over the years, but I’d never had to try and find ‘Fritz’ before, it’s teasingly more difficult, given my grasp of German extends mainly to the stuff I picked up watching 1960s war films and on exchange visits to Germany in the 1980s; so I can tell someone to put their hands up, to be quick and can order a two pints of beer and do some vague swearing doesn’t get you far with online archives in German. I gave up and had a beer. When we got back I emailed Rob Schäffer who runs Gott mit uns, a fabulous website which shows the view from the other side of the wire. Rob understands these matters, firstly because he’s a bit of an expert on Germany in both wars and secondly because he does research into exactly this type of thing. And lo and behold within an hour or two we had our man and here he is in digital paper form:

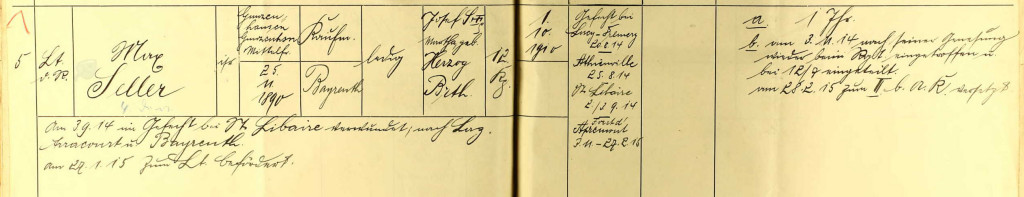

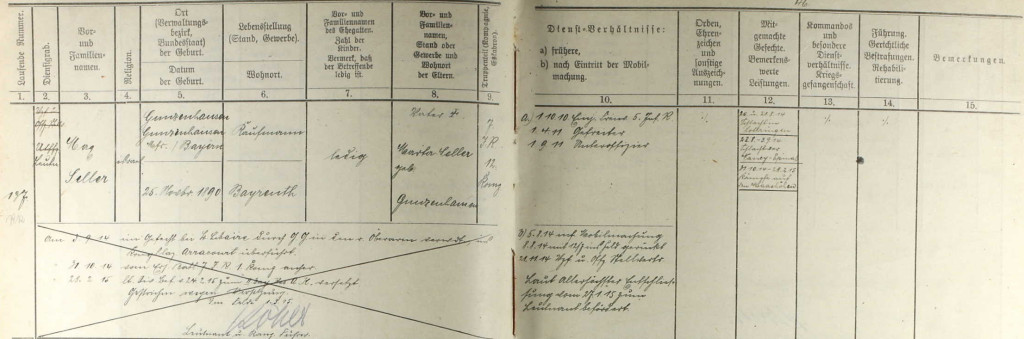

Maximilian (max) Seller was born in Gunzenhausen near Bayreuth on the 25th of November 1890 he died, Killed in action on 24th of June 1916. He would have been 26.

Max was not not married. Martha Seller, his mother was a widow. His trade is listed as a ‘Merchant’ and his conduct as ‘Good’. He served as “one year volunteer” in the Bavarian Army (“Königlich Bayerisches 5. Infanterie-Regiment „Großherzog Ernst Ludwig von Hessen“) from October 1910 to September 1911 getting promoted to the rank of Unteroffizier (Sergeant)

On the 5th of August 1914: Joined Bavarian Infantry Regiment No. 7 on mobilisation. 3 days later on the 8th of August 1914: transferred to the front. On the 3rd of September 1914 he was wounded in a skirmish near St. Lebaire; a rifle bullet to the upper left arm – Hospitalized in Arracourt by the 21st of October 1914 he had returned to front. (Bavarian Infantry Regiment No. 5, 5th company) by the 21st of November 1914 he was an Offiziersanwärter (officers aspirant) and on 27th of January 1915: promoted to Leutnant (Lieutenant). From the 19th of November 1914 to 27th of February 1915 he was the Squadleader/Zugführer in 12th company.

Regimental files do not tell how Max Seller died and only note day of his death.

Rob also furnished me with these details, which colours him in a bit more, which give us a sense of scale from their side: In WW1 his regiment had 70 officers, 361 NCOs and 3260 men killed in action, had 1 officer, 12 NCOs and 121 men dying from disease, had 1 officer, 14 NCOs and 223 missing in action. The total losseswere 72 officers, 387 NCOs and 3604 men (4063 men). By the end of the war 27 officers, 3 doctors, 176 NCOs and 1.098 men had been taken prisoner. His regiment demobilised 1st of December 1918.

This is what I think this is really all about, bringing these young chaps back to the surface for an instant, sometimes we only have facts and figures to do this, sometimes we can find a bit more, I’d love to find a photo. The day he died was ‘a quiet day in the area’ I have just read in a report from our lines, this doesn’t of course mean much in itself, he could have been leading a party out, or may have just been hit in a skirmish, you can’t tell and it’s just more or less impossible to find out.

If you have German relatives that fought in either war, which is surprisingly more likely in Britain given the number of prisoner of war camps spread across the country and indeed the immigration from Germany in the post war years, or are reading this somewhere else and want to find out a bit more about them I suggest having a look at Rob’s website. He offers a file finding service as well as running one of the best blogs on German military history anywhere on the web.