Barrack street, Norwich, is a non-place. There’s not much there to see, it’s a place to pass through, a ring road asphalt necklace choking the medieval. Apart from some tasty post war council flats and a building I once was trained to explain Richard Branson’s mortgage overdrafts (debt forever), it’s mostly building sites (Jarrolds), a gym (Greens) which is such an abortion of architecture that I would happily stand outside and lob doughnuts at the punters, plus second-hand car dealerships, dentists, the International HQ of QD, and the Department for the Eradication of Farming and Rural Affairs (DEFRA).

In the early noughties, I was given several boxes of slides and a viewfinder as a birthday present. The slides were of 1950s Norwich and unnamed seascapes. Some were utterly haunting, especially the staged still life with a budgie. I grew up in West Kent, my dad a road worker when I was born and later a rep for Ernest Doe and Sons, flogging tractors and combine harvesters to farmers whose land was fast disappearing for development into soft-estates. My mum did hair for the elderly. I’d sometimes go into her client’s alms houses and endure the smell of perm lotion ( and in return got given the little plastic swords that came in the packets) and there would always be a budgie squawking in the corner near bad oil painting replicas from Boots of doe-eyed children with puppies or standing in rags. Their budgies would always have beefy names, like Rocky or, well, Beefy.

It is these people who have vanished. A whole swathe of them went with the 20th Century, along with the many Mrs Tibbs from Fawlty Towers, coal bunkers, leaded petrol, pier end smut, light entertainment and games show hosts with names like Leslie Crowther.

What I love about these slides is the way the past feels simultaneously close and yet so far away. I’m of the generation that remembers pre-internet life, and the sobering amount of death and grief aside, I am getting a little nostalgic kick out of the Calvinistic Sunday feel of lockdown. The world was different, and I know I am not alone in feeling that odd sense of experiencing two realities in one lifetime: digital and pre-digital. I remember houses still having fireplaces and wallpaper like that of the Goodrums of Barrack St, Norwich, when people had to talk to each other and phonecalls to relatives were social occasions. I remember celery as a THING.

I meant to do more with them but then life happened. So fifteen year later here we are, with Nick kindly digitising them for Invisible Works so these faces, these brief moments in time that those faces forgot and feared being forgotten are now out there again, relit and speaking to us the way history should. It is in the ordinary, in way a mother looks at her son as he takes her photo on Christmas day, 1957 that moves me beyond any grand narrative. It is that look to the camera, with family around her in her new pinny, that raises the hairs on the back of my neck as I walk down Barrack street.

Andrew McDonnell – May 2020

Click on the image below to open the gallery view.

Andy first mentioned these to me some years ago. He is aware of my predilection for ephemera, especially old images; slides, photos, glass plates and printed matter. Through some iphone photos against a screen we both initially thought the lad in the blue jacket might be an injured veteran, he isn’t as far as we can work out now we can see them properly, sometimes slow processes are good, this one has been.

I have piles of other people’s stuff, not unlike this. It’s not nor has it ever been about ownership, it’s always been about that connection to ourselves in our environment, one of the many reasons why it’s so important to do this, it is the Museum of the Everyday exploring the whys and wherefores of the mundane, not the stuff of carnivals or kings. Recordings like these aren’t just the empty do you remember Opal Fruits? nostalgia of social media circles. Because what these found piles of slides and photographs do is give us a window into what life is still like underneath everything we do as much as they allow us to see what it was like in this instance in the mid 1950s to early 1960s; those are the rough set of dates we have for these from the boxes. And the locations; Norwich, Great Yarmouth, a foray to London, one slide of Barry Island, a handful of Gorleston, Cromer, Blickling and Suffolk.

We may not have celery in celery vases and our Christmas’ may look different, but we still pose for portraits, take selfies, stare at the sea, and watch the grain being brought in. Ultimately we’re more the same than we are different, the feelings beneath us don’t change much, the love in a family, the requirement to record, to hang on to a memory and to exist in some way after the event.

I think what I love most about these is the fact they’re so normal, from the portrait of mum wearing her new present, to dad sitting down on a straw bale with what looks like a gammy knee while mum stands in her tailor made tweed two piece, a break in a country walk. Some have a vaguely Norfolk Gothic feel about them, it’s a lovely thing, stuff to be enthralled by and bury yourself in. And I know what Andy means about Barrack Street, I inhabit a haunted landscape most of the time, mine own ghosts as a resident and the ghosts of others like the Goodrum family and the other lives I’ve peered into via my work in archives public and personal, it has quite a thrall.

I’m also always struck by the colour palette of these old Ilford and Kodachrome slides, there is something quite otherworldly about them that you just don’t get however hard you try with digital, no matter whether you let you phone or camera automatically mess about with internal recipes in whatever app you have installed, or deploy profiles in your processing off-camera, it’s very difficult to replicate, and why would you in some ways, this was then, not now. I think it’s because these are straight out of someone’s head. There is a choice of film, which you can detect in the over-zesty orange in some of the tungsten light in the interiors and some of the outdoor blues are a bit hard. But there is no straightening up, if the exposure is wrong it’s just wrong, If the focus is out that’s how it is, that’s how it looks frozen until the emulsion strips away or someone like me prolongs it all temporarily by turning it into noughts and oughts for as long as that may last.

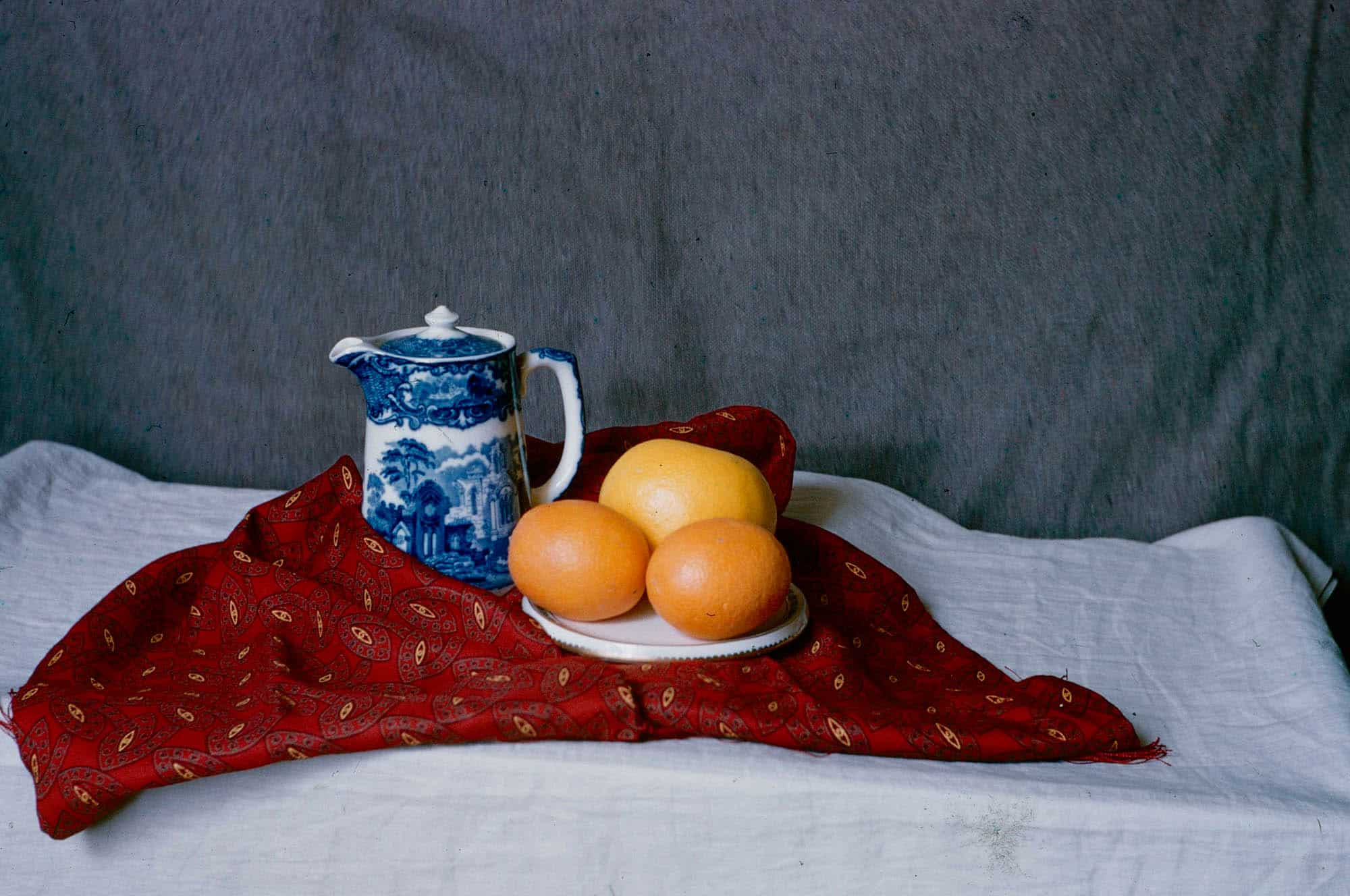

Whichever son was the photography enthusiast, be it P. or H. Goodrum (both are mentioned on the address slips), or indeed both, they liked to play, but there’s a degree of seriousness, an aptitude. His portraits have a certain something, particularly an understanding of light, the landscapes have an awareness of space, you can feel his eye in the viewfinder moving from corner to corner making that frame what it is, the deep process of exploring what you’re seeing and how that abstraction shapes the output. There are also the simple still lives, again the light is right, and that’s really what photography is in essence, it’s letting in and holding onto that light, how it shapes what we see and what we are. These aren’t mere snaps.

One of the things that’s been nice about sharing these on social media has been the comments, the detective work that has ensued, nailing down the years using visual clues like logos and CSI style debates about calendars, forensic fashion discussions, locations worked out by the familiar still visible on our ever-changing horizon.

There is a story here too, how these boxes of slides found their way to a junk shop is a mystery, orphaned as they are from their family who lived at times in Barrack Street and later in Thornham Close, it would be nice to find out who they all really are. So if anyone knows please do get in touch, and should you be family we’d really love to hear from you and flesh out the story.

Nick Stone. 2020.

I didn’t want to see the end of this photo box. I became quite obsessed. They’re bloody great. Thanks, both for sharing.

I love the one of the tractor in a field. It reminded me of Peter and Jane books. Summer! You can smell the scene.

Thank you for sharing these richly evocative photos and for your commentary.

The woman holding the boy by the tree stump, could so easily be my auntie Jean.

I am a goodrum in America but my brother has done extensive research into the Goodrum family and may be able to give some info.