I go through people’s leftovers, their old clothes, the maps of lines on their faces, sit in their seats and eat from their plates; strangers’ stuff. They are people I can’t know nor ever will in the vast majority of cases, nearly all of them are unreachable; dead, others set adrift, forgotten.

There is something terribly sad about a box of photographs in a junk shop or antique centre, and it’s like an itch. I hate detective stories and crime dramas, but there’s something oddly magnetic about a forgotten life, something that can be at least partly explored.

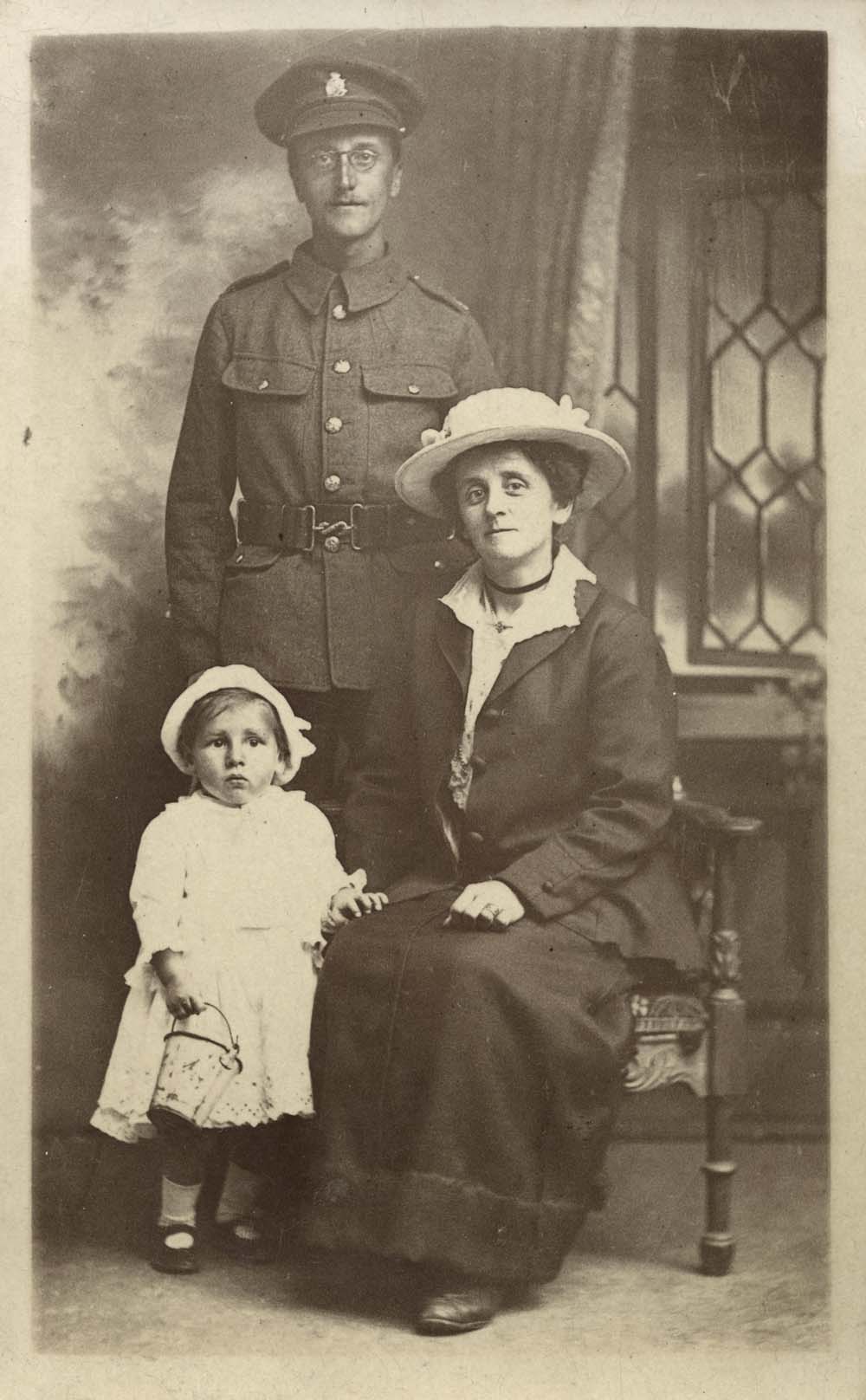

Most of the photographs I end up with are centred on the Great War; soldiers and their wives, often children too, occasionally even a blurred moving dog. And there they all are standing stiffly in front of the slow blink of the shutter eighty, ninety maybe a hundred years ago fixing them under the now crazed silver surface. Sometimes there’s a date, occasionally a postmark or a message, a name or a date or a blurred cap badge or a shoulder flash that might give a clue as to where they are from or what they were called, marked on the back of the postcard or photoback denting the emulsion. occasionally next to the pencilled 50p or £1 there’s the name of the studio where it was taken or an embossed stamp in the corner claiming copyright for a business that shut down years ago.

I’ve picked up RFC and RAF pilots, soldiers, seamen, nurses and ammunition workers. ANZACS, Krauts, flat-cheeked Flems and hairy pipe smoking Poilu, officers, gentlemen, ordinary rank and file, cheeky blighters, stout Yeomanry and the injured young and old. The names of studios become familiar, particularly the local ones. I walk past one nearly every morning, glance at the hairdressers getting ready for the day, drinking coffee in the salon window arms crossed unaware of what their shop used to be. One hundred years ago Mr Read swept his step and looked across Wensum Street before checking his watch and getting on with his day. Welcoming in the populace in their suits and hats to stand in front of painted sylvan landscapes or a sunlit window on canvas, props to lean on. If you were a soldier newly invigorated by the King’s shilling but without a uniform you could pop in and hire one for the photo

These little places are dotted about all over the reverse of our age, a time before photography became affordable, in an era where only the comfortable could have the luxury of a camera; a folding Autographic or Kodak vest pocket with expensive film and processing was an investment. We take this whole catching a likeness for granted, practically everyone in the developed world has a camera as part of a communication system built in in their vest pocket, you may be reading this on your magic camera telephone device now, chances are that around seventy percent of you are reading this on something that takes photos, that doesn’t include laptops and desktops with cameras built in. In addition we are continually monitored and recorded by surveillance cameras, and the ability to take a photo of ourselves is ubiquitous, monkeys in the landscape, grinning faces turned to the lens. Not so with these old things, the reasoning maybe similar; the recording of an event, but the deliberation seems different, the determination is to record on Halide, make soft emulsioned prints for mantlepieces and wallets the same pocket-held reminders as our smartphones hold. It is an act of creating something that won’t be forgotten; the day I signed up, the day I went away, the day I came home, the leave when I saw my family again. The proof I existed and maybe that I made it through unscathed. Existential stamps on time now cracked, fingerprinted, foxed or acid damaged. ‘Please, remember me always, never forget’.

These little places are dotted about all over the reverse of our age, a time before photography became affordable, in an era where only the comfortable could have the luxury of a camera; a folding Autographic or Kodak vest pocket with expensive film and processing was an investment. We take this whole catching a likeness for granted, practically everyone in the developed world has a camera as part of a communication system built in in their vest pocket, you may be reading this on your magic camera telephone device now, chances are that around seventy percent of you are reading this on something that takes photos, that doesn’t include laptops and desktops with cameras built in. In addition we are continually monitored and recorded by surveillance cameras, and the ability to take a photo of ourselves is ubiquitous, monkeys in the landscape, grinning faces turned to the lens. Not so with these old things, the reasoning maybe similar; the recording of an event, but the deliberation seems different, the determination is to record on Halide, make soft emulsioned prints for mantlepieces and wallets the same pocket-held reminders as our smartphones hold. It is an act of creating something that won’t be forgotten; the day I signed up, the day I went away, the day I came home, the leave when I saw my family again. The proof I existed and maybe that I made it through unscathed. Existential stamps on time now cracked, fingerprinted, foxed or acid damaged. ‘Please, remember me always, never forget’.

Usually I repair them and occasionally used to colour some in, breathing in some false new life. I don’t so much now, I still look at them, both the emulsion and the noughts and ones, upload a few, knowing if nothing else that they at least have a home for a while. The problem is if you don’t know who they are you can’t give them back to anyone they are just detached from any meaningful context, their descendents and gone, misplaced and orphaned in our world where 880 billion photos were uploaded to Facebook alone last year, the hum of servers keeping those memories alive.

Usually I repair them and occasionally used to colour some in, breathing in some false new life. I don’t so much now, I still look at them, both the emulsion and the noughts and ones, upload a few, knowing if nothing else that they at least have a home for a while. The problem is if you don’t know who they are you can’t give them back to anyone they are just detached from any meaningful context, their descendents and gone, misplaced and orphaned in our world where 880 billion photos were uploaded to Facebook alone last year, the hum of servers keeping those memories alive.

I bought some recently, a handy little message from a friend, a small pile of images, 15 in total, spanning about two years of the Great War, four portraits of two parts of one family, brothers as far as I can tell one with his wife and child, the other with his wife a girl and a boy. The other photos follow them on a vest pocket camera across Britain and on to “Serving dinner in Athlone 1918” on the Shannon in the centre of Ireland, water and tents, field kitchens and men in Great coats and Brodie Helmets pulled tight hunkered down smiling in the rain, the thin khaki edge of a slowly distintegrating Empire four years before Ireland’s future as a republic. I’ve been there, a curious place on the broad river. The War memorial to the Republican Army near the bridge, nice proper Irish pubs. The portraits are marked ‘to Will’ and ‘to Reg’, taken in Cromer in about 1917. A quiet war, he made it out I would think, the 2/3rd County of London Yeomanry (Sharpshooters) generally did, he looks an older man to me. And now here they are; castaways of a house clearance nameless in time.

More photos available to view on Flickr here.

loved reading about the lost rivers of norwich. l have a book ‘lost rivers of london’ by nicholas barton. have read it, and reread it many times, along side modern day maps. lt is one of my most precious books. l would love to look at other info regards the norwich rivers. do you know where this info might be found? best wishes.