Thomas Hubbard, Aged 52, Died 28-4-42

Norwich Garden of remembrance. Memorial cemetery. Farrow Road, Norwich.

“The date that sticks in my mind is 28th April 1942 and the time 10.30 At that moment I was in the Anderson shelter in my garden on St. Martins Road, Norwich (near to Wensum Park). With me in the shelter was my mother, stepsister and my father (Thomas). My father had not been called up to fight because he was aged 52 and too old. He had lost a lung in the first World War.

“The date that sticks in my mind is 28th April 1942 and the time 10.30 At that moment I was in the Anderson shelter in my garden on St. Martins Road, Norwich (near to Wensum Park). With me in the shelter was my mother, stepsister and my father (Thomas). My father had not been called up to fight because he was aged 52 and too old. He had lost a lung in the first World War.

My job, when the siren went, was to take water in a very strong jar into the shelter. We also had food there.

That particular day, while we were in the shelter, we suddenly heard ‘planes and then bombs dropping like rain. My house collapsed on to the shelter and my father’s head was very, very badly damaged. There was so much blood and he died in the shelter. For two and a half days my stepsister, my mother and me sat in the shelter. We were up to our necks in water because a water main had been hit and as a result everything had become flooded. I was only ten years old at the time and I felt I was going to drown. The air-raid wardens finally dug us out. We then discovered that not only had my Dad died in the raid, but many children in the street had as well. Many of these children had been my friends.”

Bernard Hubbard, his son.

Courtesy BBC People’s War

WW2 People’s War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found at bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar

This incident haunts me. It is one of the places, for me, where the reality of the story of the Baedeker Raids of Norwich Blitz spiral outward. Thomas died within 20ft of our back gate, he died in an attack that tore the back out of our house, reduced two of our row to dangerous structures that were later demolished and rebuilt. The result of a 1000kg bomb, one of a handful dropped during the raids which landed somewhere near the ARP station at the St Martin’s Road Gate to Wensum Park. It destroyed a whole row of terraces on St Marys Road, taking the Potter family with it. The blast damaged St Martins to a point where complete demolition was the only way to deal with the scale of the destruction. Aerial photos from 1946 and 47 reveal a flat area of sandy soil and Fire Weed.

The ‘Hermann’ as these 100kg giants were known would have fallen silently; no whistle attached unlike the smaller bombs, which had small cardboard or metal tube attached to the tail. As the bomb falls the rushing air plays it, it is designed to terrify, create fear, demoralise the recipients, maybe force them to run. These big ones had no warning, just the rushing sound as they displaced the air propelled only by mass and Gravity, then the thump and the bang. The blast is unlocked as the energy bonded in the High Explosive is released by the detonator firing the charge, this shatters the case outward scattering spinning metal splinters in all directions from within the ground where the bomb had embedded itself, throwing a plume of masonry and debris high into the air upward, outward, through and over the surrounding houses. Even distant windows were shattered and tiles riffled, chimneys empty their contents into living spaces, plaster falls off lath, rooms are ruined. Nearer the centre of the blast wave bowed brickwork and twisted wooden roofs, clods punching holes in walls, air is sucked out of rooms, people lifted and dropped. Those in public or Anderson shelters, under the table or a Morrison would have felt the thump almost instantaneously followed by a thundering roar vibrating the ground and walls around them, the dying reverberation of the sound then punctuated by the bangs, pops, tinks and thumps of falling debris. And at the centre houses collapse, whole walls are thrown flat or fall, roof-lines collapse. Time stops.

When I look out from our back door I can see the row that isn’t there on St Mary’s, now a row of post-war garages growing outward from the Norwich Blitz, I can see the row on St Martins that replaced the house Thomas lived in, where he pottered in the kitchen making tea, sat in a chair reading in the afternoon light, or looking out of their rear windows down the long garden at the row behind, at the window I’m standingin drinking tea at looking out across the years to the place where he was.

When I look out from our back door I can see the row that isn’t there on St Mary’s, now a row of post-war garages growing outward from the Norwich Blitz, I can see the row on St Martins that replaced the house Thomas lived in, where he pottered in the kitchen making tea, sat in a chair reading in the afternoon light, or looking out of their rear windows down the long garden at the row behind, at the window I’m standingin drinking tea at looking out across the years to the place where he was.

We’re within touching distance, I can almost sense his eyes on mine and that moment is within touching distance too. The brickwork of our house changes, the soft old Norfolk Reds, the originals placed here in 1905 – building housing for the shoe factory workers, the Clickers, the Bootbinders and the Finishers now remembered in the street names off Drayton Road. Those soft bricks are knitted into harder brick from 1949 from eight courses up, right up to the roofline. When we moved in we picked dated newspaper remnants from voids behind skirting. You can still follow the damaged lines with your eyes along the back of the row the replacement houses, the two missing teeth punched out – rebuilt in a child’s drawing of Edwardian style, the end of the row where the large detached residence is replaced by two early 1950s semi-detached houses. so here it is, the visible archaeology in the street, the remnant of an event, persistent in memory, the echo of lives.

Another wistful and thought provoking piece Nick. You have a great sense of place and convey it very well in your writing – you always make me want to do that daft thing of getting straight into the car to go and stand in that place and breathe the same air. Please keep it up.

Cheers,

David

Thanks David, much appreciated.

hi I am Bernard Hubbard grandson and thank you for this piece. the family still live in Norfolk. I work in Norwich and pass the area lots.

thanks for adding to my grandads story the family still live in Norfolk and remember grandad telling me the story.

Hi Ian, thanks for the comment, sorry for the delay in responding here and on Facebook. I think of the family often, also the Potters who lived just around the corner. If you have any further information, please email me, it would be nice to continue the story, I’d also be interested in any photos you may have of him and your grandfather, quite often that can complete a story rather well.

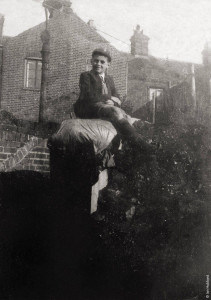

Hi I’m glad you used the photo of grandad sitting on the anderson shelter a few weeks before the terrible incident happened. If you can use the photo of Thomas Hubbard that would be great for future family members to remember him and his wife Blanch.

Nick, I read the article and Twitter thread about Royal Potter and his family. He was my 3rd cousin (1x removed). There were many Potter’s living in that area; my great grandfather Herbert was rehoused from nearby Albany Road following the same raid. My grandmother was evacuated thereafter being 10 months pregnant with my father. In the house with the Potter’s was Lillian’s sister Ethel Jopp. Ethel wasn’t visiting from Yarmouth she lived with them after the death of her husband on 26 Apr 1941. He was Sergeant 926491 Walter John Henry Jopp (Royal Artillery). They had previously lived in Cambridgeshire and at 321 Sprowston Road.

I have just read this piece. It is likely that one of the ARP Wardens who dug the family out was my grandfather. He was a warden based at Wensum Park. His name was Francis King.