St Theobald, Hautbois

In 1982 we were starting sixth form, it’s an odd piece of territory that whole mid-teen bit of the timeline. One chunk of life you are used to, the uniformity and structure of school lessons ends, then there’s a summer of free fall. Suddenly everything is properly jutting out into adulthood, people you know have gone off and got proper jobs or apprenticeships being electricians and clerks, others of us were preparing for the real education of thought rather than the passing of exams, the move into A levels, weekend jobs morph into summer-long methods of torture. And as college starts new people turn up along with a lack of uniform and free time to ‘study’ in. One person who started had recently moved up from near London so his mum and dad could take on a corner shop in Coltishall, damn those expansionist from the cosmopolitan south.

He was cooler than us, had been to an ethnically diverse school that wasn’t full of the kids of farm labourers, factory workers, rural vicars and coppers. We existed in this apparent bucolic, desperately white, nearly middle-class land out in the barley, wheat and sugarbeet fields, surrounded by insomniacs driving pea-viners, the smell of vegetables being processed, and the clatter of truck beds being made. He and I had similar spiky and shaved haircuts and a taste in music that overlapped well outside the deeply trodden pathways of heavy metal, skinhead, prog and country so familiar in the small towns of rural Norfolk. That was enough. We were good friends immediately, sharing a bag of big fat Chinese takeaway chips outside in the market square, the likes of which Norfolk seemed to have only just discovered. We moved in a small circle of people with similar tastes in crimpers, drainpipe jeans and biker boots, it all fitted. We, like all teenagers, aliens in our own landscape together and apart.

A year on and we were well into our A Levels, the weekend diversions of parties, gigs and odd pubs in corners of the Norfolk countryside around us, we headed out into the agricultural hinterlands towards Norwich, around the broads and up towards the coast. We’d formed a fledgling band, were writing what now strike me as remarkably moribund New Wave-ish tunes each dutifully recorded on cassettes and bashed out to anyone that would listen. We hung around the pubs that would serve us while we waited to fall out of the nest.

The summer of 1983 was warm, we were old enough to be allowed a fair bit of freedom, some people already had bangers to knock about in, parents full of trust wanted to get away for a week or two without the burden of teenagers. Including his. We had a few running a shop lessons which neither of us really needed – I already worked in a garden centre and had a Maths ‘O’ level of sorts – they put us in charge of the Mace store in Coltishall. It had a cold counter, some vegetables, tinned goods, sweets, cigarettes and an off-licence.

We had order books to fill in, shelves to stack, We dealt with meat for old ladies (which wasn’t and isn’t a euphemism) learning to control the cut of the spinning disk. We bagged up onions and spuds in pounds, stacked cans in shelf units and stuck labels on things with a price gun. We dutifully filled in a tab of all the things we borrowed from the shop. It was the week I went vegetarian, partly because of hunting and all that stuff. But also because I’d been invited to a hunt ball by a posh girl which had annoyed me, ‘fuck that’, seemed appropriate, so I didn’t go and stopped eating meat in a po-faced way to prove a point. It was point scoring that lasted me into me early twenties before I met a chicken and ate it and jumped back on the tracks of being an omnivore. I still detest hunting and all the classist nonsense that goes hand-in-hand with it.

Outside the selling comestibles, fag breaks and dicking about in the shop it was a week of loud, probably on reflection, fairly odd music, a Velvet Underground phase was happening, along with a resurgence of The Scars and other scratchy post-punk. We managed to host the odd party, experimenting with the alcoholic stock of the shop interspersed with pub crawls between the numerous Broadland tourist pubs that dot Coltishall and Horstead; mingling with the families from the cruisers tied up at the common between the Rising Sun and the old long since closed Anchor. This was accompanied by visits from various friends to assist in eating and drinking the dwindling stock.

It was the week I also realised how much I was interested in the past as much as the possibilities of living in a off-licence with a big stereo and a mate who liked rum and black and lager chasers and mucking about. It occurred to me even then that I may have bungled what subjects I chose about 4 years before. History had left me cold at school, leaning on a hot gurgling radiator and dozing along to a list of kings and queens hadn’t appealed – that regimentation and reliance on these boring lists. It’s not that I regretted picking geography, the subjects are meshed into each other anyway, but I hadn’t really fully realised that until this fortnight in August in 1983 – how our pasts are as much about the depth of place as they are time. A friend came over to visit. She was in my English class and lived near the coast up at Beeston Regis surrounded by all the history that lurks there; the priory, the churches and Bronze Age hard memories in the soft rise and fall of the ice carved land. She intended to study archaeology at university which required showing some willing beforehand. It was decided field trips to somewhere nearby would be good, particularly if it also involved a picnic and as much lager and cider as we could carry.

It was the week I also realised how much I was interested in the past as much as the possibilities of living in a off-licence with a big stereo and a mate who liked rum and black and lager chasers and mucking about. It occurred to me even then that I may have bungled what subjects I chose about 4 years before. History had left me cold at school, leaning on a hot gurgling radiator and dozing along to a list of kings and queens hadn’t appealed – that regimentation and reliance on these boring lists. It’s not that I regretted picking geography, the subjects are meshed into each other anyway, but I hadn’t really fully realised that until this fortnight in August in 1983 – how our pasts are as much about the depth of place as they are time. A friend came over to visit. She was in my English class and lived near the coast up at Beeston Regis surrounded by all the history that lurks there; the priory, the churches and Bronze Age hard memories in the soft rise and fall of the ice carved land. She intended to study archaeology at university which required showing some willing beforehand. It was decided field trips to somewhere nearby would be good, particularly if it also involved a picnic and as much lager and cider as we could carry.

The three of us ended up in Great Hautbois, less than a mile away from the shop. It is an uncentred village if you work outward from the old church. What there is is perched on the slight valley slope away from the flat damp floor of the Bure Valley and its older settlement traces. We were looking for the site of a medieval moated manor house also known as The Castle, we found it. It’s not exactly obvious and we couldn’t get near it because of fences and some flooding from a thunderstorm and being 17 and slightly useless at everything. At that age it wasn’t much of a castle to look at anyway; a tree covered bump in a water meadow. But it was exciting to a would be archaeologist and it pricked my interest in the unseen in the landscape, a sign of human habitation from the twelfth century lost in a copse. It hides more too, there was a Pilgrim hospital – it may even be the same site as the castle. It would have attended to any Pilgrims at St Theobald, St Tibbald of Hobbies, and was built by the Norman Lord and landowner Peter de Alto Bosco directly on the route between Walsingham and St Benets. There is some argument about whether it was a Great or Little Hautbois which hosted this tale but it seems like it was here in these fields. The lesser settlement is not far up the road, it has also lost its church and has a fragmented and scattered settlement. Before the hospital and the castle there are other stories of it being built over the site of a Roman Villa, and evidence lies in the bricks in the church in the reused Roman material. The layers are all here, hidden in the beech trees and damp willows, between the daffodils and the gravestones.

The church of St Theobald in Hautbois was part of our target that day. It is a semi-ruin, isolated on the valley floor away from any settlement, set on a rise amongst the tussocks of the grassy marsh that surrounds it, sitting in the defensive curve of the river as the Bure wends along just below, encircled by the rising land that forms the spurs of flood plain walls. We were aware of the church already. Historically it had a reputation – possibly made up – A place that the local pagans went and did their nocturnal tribal jumping about stuff. And sure enough when we got there in the middle of the open roofed Nave there was a burnt patch on the grass and some empty cans of lager, a sure sign of proto-satanists or something. We haunted the ruins for a while as teenagers are wont to do. She pointed out various bits and bobs. Then we had a picnic of stuff from the shop and cans of cider behind the church in the molehills and gravestones and stared across the valley at the castle that is there but isn’t and talked about how dreamy Julian Cope was and Teardrop Explodes.

The church of St Theobald in Hautbois was part of our target that day. It is a semi-ruin, isolated on the valley floor away from any settlement, set on a rise amongst the tussocks of the grassy marsh that surrounds it, sitting in the defensive curve of the river as the Bure wends along just below, encircled by the rising land that forms the spurs of flood plain walls. We were aware of the church already. Historically it had a reputation – possibly made up – A place that the local pagans went and did their nocturnal tribal jumping about stuff. And sure enough when we got there in the middle of the open roofed Nave there was a burnt patch on the grass and some empty cans of lager, a sure sign of proto-satanists or something. We haunted the ruins for a while as teenagers are wont to do. She pointed out various bits and bobs. Then we had a picnic of stuff from the shop and cans of cider behind the church in the molehills and gravestones and stared across the valley at the castle that is there but isn’t and talked about how dreamy Julian Cope was and Teardrop Explodes.

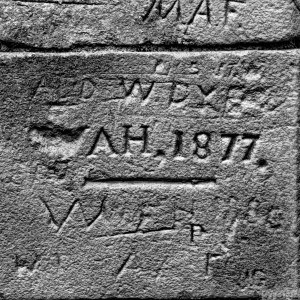

I’ve been back several times since, it is probably more well-visited than I thought at the time, a regular stopping off point for photographers and antiquarians looking for something vaguely gothic and gloomy. It is actually rather lovely if a little sad and unloved sitting on a bump in the flat marshy grassland. It always feels like it may have a history that predates the Christian church on the site, a previous chapel or a burial ground being reused and reused over and over maybe. It almost certainly has it’s feet in the Saxon period, perhaps a wooden chapel then the stones. The round tower is slightly later, made of flint, probably Anglo-Norman. The original nave is small, and the chancel which is still roofed has been converted into a mortuary chapel and then since left locked. the building dates back to the eleventh century with medieval goings on in terms of alterations and the addition of an aisle in the fourteenth century. Some of the past clings on, there are signs of decoration, some dog-toothing and bits of carving cling to the flint. Graffiti marks the remains of the ashlar dressing, most of which date to those who haunted the building after the deconsecration and loss of the roof, than before. It ceased to be used in the 1860s and was abandoned, roof torn off to decrease taxation on the parish like a chest opened up, the heart beat slowly stopping inside.

I’ve been back several times since, it is probably more well-visited than I thought at the time, a regular stopping off point for photographers and antiquarians looking for something vaguely gothic and gloomy. It is actually rather lovely if a little sad and unloved sitting on a bump in the flat marshy grassland. It always feels like it may have a history that predates the Christian church on the site, a previous chapel or a burial ground being reused and reused over and over maybe. It almost certainly has it’s feet in the Saxon period, perhaps a wooden chapel then the stones. The round tower is slightly later, made of flint, probably Anglo-Norman. The original nave is small, and the chancel which is still roofed has been converted into a mortuary chapel and then since left locked. the building dates back to the eleventh century with medieval goings on in terms of alterations and the addition of an aisle in the fourteenth century. Some of the past clings on, there are signs of decoration, some dog-toothing and bits of carving cling to the flint. Graffiti marks the remains of the ashlar dressing, most of which date to those who haunted the building after the deconsecration and loss of the roof, than before. It ceased to be used in the 1860s and was abandoned, roof torn off to decrease taxation on the parish like a chest opened up, the heart beat slowly stopping inside.

The graveyard is still consecrated and as I understand it still takes burials even today including some inside the church itself whose function has become almost more of a mausoleum from the family at Little Hautbois Manor. The church itself is the same as I remember it, the roof open to the sky and wheeling birds blowing like black rags, bare trees as a backdrop and the clouds blowing across the flat basin of the shallow valley and the tussocks which give Hautbois its name.

Walking back there is a pond just off the track you pass Golden Gates pond, it could be a village thing or just as likely a marlpit, dug to extract the chalky clay to keep the PH of the seasons running correctly in the fields. Cam Self once told me of a local folktale of gold hidden in the depths, the plated entryway to the castle hidden from those who might seek to steal them in the turmult of the centuries that followed.

Addenda:

A quick note on the name Hautbois, in the vernacular pronounced Hobbis. There are a variety of stories that relate to the name, most of the common ones on the internet are misconceptions based on whether it comes from the Alto Bosco family name (latin: High Wood). The word Hautbois a word for Oboe in Medieval French Haut Bois or Hoboy which also means High Wood. It is to be frank, confusing. However the name Hautbois predates Peter de Alto Bosco who founded the hospital here in the mid thirteenth century and even William de Warenne (late eleventh century Norman lord). It is listed in Domesday as such. It is believed that the name is Saxon and comes from a contraction of two Old English words; Hobb – meaning hummock or tussock, and Wisce meaning marshland giving the name Hobuisse/Obuuessa. This probably refers to the tussocks in the marshland or the mound the church stands on, the latter seems unlikely as there are plenty of alternative words for mound in OE, the former much more likely. if you go and have a look you’ll see that this is environmentally consistent with the Bure valley here. It is likely to be Anglo-Saxon or Anglo-Celtic and is quite unusual. There are quite few interesting place names in the area, including a few Anglo-Danish such as Belaugh and Bylaugh. This is though for another day.

It is possible via some circuitous and slightly fuzzy thinking that Alto Bosco may be a Norman version of a location based surname, because Norman lords quite frequently took the names of the manse they had bought or been given. If we consider names like de Parr which tends to come from the Manor of Parr in Lancashire, and forms all sorts of variants, including Parr, Deparr, Parry, Perry. So just maybe Haut Bois/Alto Bosco is an idiomatic expression of Hobuisse/Obuuessa in Norman French. I don’t know enough about the family to comment as to how true this might be, but there are also records that link the medieval composer John Hamboys/Hanboys in the 14th century who also maybe John Alto Bosco. It’s all slightly confusing and delicious because of it.

From a Topographical History of Norfolk by Blomefield, further reading reveals it is almost certainly a latinised version of the French from the Phonetic matching from Hobuisse to Haut Bois in Norman French.

Extract An Essay Towards A Topographical History of the County of Norfolk: Volume 6

The Manor of Hautbois-Magna,

Belonged to the Abbot of St. Bennet at the Holm, one part, of the gift of King Edward the Confessor, and of Elgelwin, a Saxon ealderman or thane, lord of it, under that prince, and the other, of the gift of Ralph Earl of Norfolk, when he granted the burial of his wife to that monastery, with the King’s consent; this part was held of the abbey at the Conqueror’s survey, by William de Warren, of whom Ralf Stalra held it, and the other part was held by Ralf de Beaufoe, of whom Eudo held it; the whole village being then six furlongs long, and four broad, and paid 2d. to the geld or tax, towards every 20s. raised by the hundred.

Soon after the survey, Herman held one half, under the abbot, at the will of the convent, but his son,

William, who took the sirname of De alto Bosco or Hautbois, was infeoffed in the half of Great Hautbois; which he was to hold of the monastery, at half a fee; he had also all Little-Hautbois, with the Abbot’s land at Calthorp, the land of Ulf, and the land of Ralf in Erpingham, to hold at half a fee more, and had the stewardship of the abbot, granted him by Alfwold, abbot there; his son

William was a great man in his days, being very much concerned for the affairs of the monastery all his life time; he had several sons, as Peter, William, Thomas, &c, from whom issued several branches of the family, but the principal estate went to his eldest son,

Sir Peter de alto Bosco, or Hautbois, who was a knight, and paid at the rate of a quarter of a fee for his manor here, to the Earl Warren, his chief lord, of whom he held it; he appears to be very old in 1234, and died about 1239, for in 1238 he released by several deeds to the Abbot of St. Bennet’s all his right in the manors of Thugarton, Thwait, Antingham, and Shipden, and in the hundred of Tunsted, and in the offices of the stewardship and procuratorship to the monastery, for 17l. a year, to be paid him for life, for his better support in his extremity of age; he was founder of the Mason Dieu here, and gave the advowson to Coxford priory.

Special thanks to Laurence Mitchell of East of Elveden and Elizabeth McDonald for making me think that through properly.

Refs: Monastum Anglicum. David Lays, Norfolk Placenames. Dictionary of placenames in Great Britain. An Essay Towards A Topographical History of the County of Norfolk: Volume 6. (British History Online)

All content © Invisible Works.

The king sits on his face buttons all askew

All wrapped up the same

All wrapped up the same

They can’t have it

You can’t have it

I can’t have it too

Until I learn to accept my reward

Princes stand in queues they stand accused

Death in solitude like Howard Hughes

All wrapped up the same

All wrapped up the same

Silence has it

Arrogance has it

I can have it ooh

Until I learn to accept my reward

Suddenly it struck me very clean

All wrapped up the same

Ho usato il traduttore Google per leggere. Le vorrei chiedere una cortesia: mi saprebbe dire chi era San Teobaldo? Era di nazionalità francese o veniva da una famiglia inglese. Era Monaco oppure vescovo? Mi sarebbe utile saperlo per concludere delle mie ricerche che riguardano San Teobaldo di Provins dell’XI secolo. Grazie