There is a darkness in woodland, hiding in the shade of the green canopy, something that retracts in the sunlight in the corner of your vision, beyond the growing and shrinking of the shadows, the greening, then yellowing, then bareness, with each revolution of the earth on its tipping axis. Beyond the sterility of the needle carpets of the pine stands in the managed farmed forests. It is in these wilds, between the thickets and the trunks that folklore, fairytales and legends grow: Babes in the Wood, Hansel and Gretel, Vasilisa the Beautiful and Baba Yaga, Genoveva, Snow White and even the Epic of Gilgamesh reside in these spaces.

It’s hidden in the words of folklore, poems, songs, fairytales and stories; resides in place-names, leaks through into the things we understand, twisting them and changing them. These slabs of life in our sterile farmland carry a weight beyond wood and wildlife; a breadth and depth of history you can sense and if you go equipped. The dimensions of woodlands through time stand out as proud as the raised earth boundaries dug here in medieval times which can still be traced off through the shadows filtering off into the trees away from the entrance cut.

Wayland Wood lies just to the south-east of Watton in Norfolk, either lending or taking its name from the old Wayland. My instinct for romance of our untethered human footsteps through these roots and leaves prefers the former, and the vague guess-laden science borderlands of naming conventions and toponymy as a subject in itself point at hundreds taking their name from somewhere and that where would appear to be here. This 84 acre triangle of woodland sitting next to the buzz and snore of the A1075 winding off towards Thetford seems to have obtained this iteration, possibly one of many from the Danes; Wane lund; a sacred grove. Curiously the name has back-formed into another word-pairing, Watt and tun a medieval hare and barrel, the symbol the town lives under still.

There are hints here of a life before the Vikings and Saxons; a Middle Bronze Age barrow sits nearby on the edge of Watton on the old RAF radar site, dug in 2010, it contained a Bronze Age cremation urn, other cremation evidence, and axe heads. It had also been reused, the dig turned up a Roman Skeleton lying on it’s side, dated from somewhere between the 1st and 4th century, it’s now housing. The B1108 from Norwich beats a grey line accompanied by the white regular blip of milestones along the roadside, at least in part it seems to plot a Roman road from Denver to Caistor St Edmund. This is in essence a farming town, a marketplace and would almost certainly have existed as a community before records name it as Wada’s Tuna with its butter market before too the Norman’s threw up a new church in stone over whatever it obliterated. We’re here, right back to our relatives in the Mesolithic. As it all these soft untouched landscapes, who knows what sleeps below.

Driving south out of Watton there’s a sharp turn off the road into a circular, loose-gravelled bowl. There’s nobody here, just a motorbike, cooling engine ticking gently. The odd car slides past, another droning motorbike in the distance. A lad emerges from the woodland, he wears leathers and I detect a faint smell of weed over the sweet smell of parsnips from the fields nearby. I start to wonder what I’m doing under the thick darkening patches of the August cloud, having filled my head with the real-life murder, death and folkloric ghosts of this place into the small hours of the morning. He smiles loosely at me and we trade an ‘ellomate for an orlright in the arch of hazel trees, his stance as slack as his face he lopes off to the bike, slides an open-face helmets on, swings a leg and sits astride and guns it before vanishing to rejoin the tarmac sliver south. I trace his progress by ear as the sound of gear changes recedes towards Thetford, until I’m left standing in the quiet, just me and the birds.

And so I step in, a step from the 20th century through a threshold that marks the medieval boundary. Here flattened by spades and feet, a splay of loose metalling from the car park trodden into the muddy path alongside a johnny wrapper, a bottle cap or two. It’s signposted; a board says ‘No dogs’, luckily mine is snoring, stinking and dreaming of hares at home. A map shows Norfolk Wildlife Trust ‘circular nature walk’; there’s no getting lost in modern life you’d think, you watch me, I stumble at every divided path inside.

It is rather beautiful, tightly fenced by growth. Swathes of low plants where the coppiced hazel hasn’t muscled in. In places the branches bends over the path forming būr like birdcages of branches, patches of light and trees followed by thick undersea pools of moving green fading off into almost black caves on side paths cut by deer through the flexible bars – alleys cut off the main drag and vanish into nowhere, paths split and divide. If I had bread or stones I’d leave a trail. It’s that or live on golden pheasant, berries and cobnuts.

Wayland Wood is alleged to be one of the oldest pieces of woodland in Britain, akin to Sherwood; they have become linked via an entwining of two different and unrelated strands of folklore. This wood is also the site of the story of the Babes in the Wood, the popular evergreen fairy tale in its true form happened here, possibly actually happened or possibly happened as a parable of one of several things, or possibly didn’t, it’s hard to tell folk tales being what they are. At some point in the last 150 years, in an attempt to pad out the slightly thin narrative elements of an alleged local double child murder, make it somehow acceptable for Christmas entertainment, Maid Marion and elements of Robin Hood were sewn on like some Frankenstein’ pantomime. The story shifted away from its dark root, turned into an entertaining moral tale and then settled into cartoon mass-entertainment – travelling from fable to fabled to Roy Hudd and Geoffrey Hughes, Jack Tripp, June Whitfield or Les Dawson, arms crossed gurning for laughs, and that’s no bad thing.

The story first appeared in writing in Norwich in 1595 as a ballad, printed by one Thomas Millington originally titled The Norfolk gent his will and Testament and howe he Commytted the keepinge of his Children to his own brother whoe delte most wickedly with them and howe God plagued him for it, which doesn’t really fit on pantomime posters terribly well or attract an average family audience. In the original ballad the ending is somewhat darker, and the fact that it’s based on a true story makes it darker still.

About a third of the distance from this frantic crush of oaks, hornbeams and hazel to where Wayland Prison and Griston sits in the sugar beet, kicked by the toe of RAF Watton, lies Griston Hall. This is the location that really carries the story. The de Grey family were a line of the Norman de Creully family. They owned the hall and land including what was then probably a much more extensive area of woodland. Thomas De Grey died in 1562 and left the hall and its considerable estate to his young son Thomas, then 7. He was made ward of the crown and a marriage arranged, a standard high caste practice in Elizabethan England. At the age of 10 he married Elizabeth Drury of Carbrooke the 16 year old niece of Sir Christopher Heydon of Walsingham. There was apparently a rift in the family, largely along religious lines. Robert the uncle was a Catholic recusant; refusing to attend protestant church services, bravely so really in an area that was largely unsympathetic to his beliefs or right to practice; this was at a time where in East Anglia less than 5% of the population were catholic. He had been cut out of the will unless he recanted and apologised for the offence to his brother.

In 1566 Thomas and his sister visited Temperance Carew their father’s second wife. She lived at Baconsthorpe and had remarried Sir Christopher Heydon. Temperence was Elizabeth Drury’s aunt by marriage to further confuse the already vaguely incestuous set of family ties in the local gentry. Robert de Grey stood to gain from the death of the boy, inheriting the estate he felt was his due from his brother via his nephew. And in 1567, die he did. The exact circumstances now unknown, unrecorded as far as I can see.

Robert took the estate, and went on to try and claim the dower lands of the young Drury girl. He failed after a huge and expensive legal squabble and had to forfeit some of the estate at Griston. It would seem that the locals were up in arms about the story, he was marked a murderer and spent the rest of his days living in misery. In the true form of a parable works; jailed for recusancy, fined and imprisoned, his sons tried to rebuild the family fortune by privateering and drowned. He died broke and broken.

So whether this was in fact just plain greed or if it sits with one buttock in a nasty dank little pool of anti-catholic propaganda, a sectarian fit-up job is open to question. Crime being what it is; you can walk into a bookshop, watch a soap, pick up a newspaper and see how well loved these ‘feet-in-fact – head-in-fiction’ stories of intrigue, murder and the complex ebb and flow of marriages and relationships are still to this day.

Whether the babes made it to Baconsthorpe is a mystery, they may have died there, or perished on the way back, or it may have been a ruse and they may have never gone at all and merely been either murdered by hired hands in Wayland Wood or dumped there, a few days earned by hiding one story in another. There is no way of telling and little hope of ever really establishing any proof of where they died beyond the fact that folk-tales have memory, they are in fact part of how we remember. Every truth is diminished and yet grows by whispers, and eroded by repackaging into a good tale to tell and sell, you only need to walk into a bookshop or turn on a soap opera to see these stories of murder, and intrigue still fly off the shelves. But it strikes me there’s something in this that places it here, in these twisting thickets, locked in the branches suspended between the dark deer paths of the undergrowth and the sunlit pools of the clearings, it will be here for as long as the wood survives.

In the life of the tale, somewhere between what we think happened and the he’s behind you jokes where the writhing story shakes off the darkness. There is a flickering moment in the late 1590s when Thomas May who had recently bought what would become known as the Wicked Uncle’s House, sat down with and wrote the story down, and it gained a life of its own, it became what Millington printed. The sinewy bark of the growing story thickens and starts to set in the shape we recognise from Christmas pantos, Mother Goose and Disney. Griston Hall absorbed some of it, carved fireplaces told the tale in tableaus well into the 19th century, now lost. The Wood back-formed a new name, Wailing Wood, after the ghostly cries of children heard at dusk, just when the foxes are heading out to play.

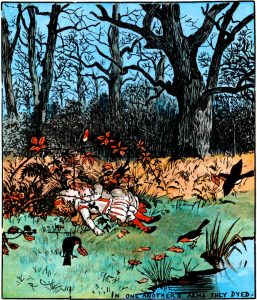

In the folktale, there is a massive Oak, they were spared the indignity of being murdered by the squabbling assassins and crawled into a gap in the roots where they died of starvation. A robin flew down and covered them with leaves as is the mythical way with this special little bird. They flutter in a special place in our pantheon of folklore; protectors of those in purgatory they burnt their breasts whilst giving water to the suffering, they pulled thorns from Christ, staunched the blood of the legions lance, you must never harm them or break their eggs for fear of bad luck, if one dies in your hand you will suffer tremors, they reveal themselves as the spirits of the recently dead to those who grieve. They inhabit our poetry and writers including Shakespeare allude to them. To Thor they are the sacred storm bird. And they hide all this in that plain verse bashed out on a primitive platen in Norwich.

The oak tree in Wayland Wood where the locals maintained the bodies were allegedly found was struck by lightning in 1879. It had become so famous because of the repetition and spread of the tale that people flocked to gather momentos from the shattered hulk, a splinter of a story taken home. Folk tales however dank rarely harm a local economy in the long term. You will find it on the village signs in Griston and Watton. Babes in the Wood has lost none of its potency although the black is watered down to a pasty grey in local business names. The site of the grand oak is now lost somewhere, ground down into the soil below the refreshed growth of new bowers springing from it’s acorns like hobs.

The oak tree in Wayland Wood where the locals maintained the bodies were allegedly found was struck by lightning in 1879. It had become so famous because of the repetition and spread of the tale that people flocked to gather momentos from the shattered hulk, a splinter of a story taken home. Folk tales however dank rarely harm a local economy in the long term. You will find it on the village signs in Griston and Watton. Babes in the Wood has lost none of its potency although the black is watered down to a pasty grey in local business names. The site of the grand oak is now lost somewhere, ground down into the soil below the refreshed growth of new bowers springing from it’s acorns like hobs.

For every Redbreast’s feather the oak has a thousand leaves, each one a strand of folklore so rich it is important in nearly every faith in the climates where it is found rising from the soil gaining solidity. From Druids via Vikings and Saxons to Christians. And if you study the Arne–Thompson–Uther (ATU) index of folktales, although it fits in somewhere near Hansel and Gretel, around ATU 273, it is a very individual tale too, it’s not quite a fit; there’s something more here, the cold whisper of truth. That aside, in this grand lineage of story-telling, It is not beyond belief that this also has a deeper history, some of the symbolism may hint back at older pre-Christian beliefs, to times of cycles of death and rebirth under the oaks. Akin to bog bodies, but in the forest, deep in the woods, children left to fend for themselves under the huge trees.

Back in the wood the temperature drops, the pools of light fill with the promise of rain and ink. I head out taking the correct path at a split I had forgotten. I pass a boy and a man walking, and there is a sudden pang of the reality of the story underneath. As I reach the car the cloud starts to fill in and spit, I pull away in the car and circle back up around the warren of side roads up into the countryside, pull over in the corner of a field and stare back through a curtain of fat drops at the wedge of darkness that cuts across the line between soil and sky.

Wadden

Beorn sceal gebidan, þonne he beot spriceð,

oþþæt collenferð cunne gearwe

hwider hreþra gehygd hweorfan wille.

Ongietan sceal gleaw hæle hu gæstlic bið,

þonne ealre þisse worulde wela weste stondeð,

swa nu missenlice geond þisne middangeard

winde biwaune weallas stondaþ,

hrime bihrorene, hryðge þa ederas.

Woriað þa winsalo, waldend licgað

dreame bidrorene, duguþ eal gecrong,

wlonc bi wealle. Sume wig fornom,

ferede in forðwege, sumne fugel oþbær

ofer heanne holm, sumne se hara wulf

deaðe gedælde, sumne dreorighleor

in eorðscræfe eorl gehydde.

The Wanderer

A wise man may grasp how ghastly it shall be

When all this world’s wealth standeth waste,

Even as now, in many places, over the earth

Walls stand, wind-beaten,

Hung with hoar-frost; ruined habitations.

The wine-halls crumble; their wielders lie

Bereft of bliss, the band all fallen

Proud by the wall. War took off some,

Carried them on their course hence; one a bird bore

Over the high sea; one the hoar wolf

Dealt to death; one his drear-checked

Earl stretched in an earthen trench.

Poetic translation by Michael J. Alexander, 1983 edition of Old English Literature.

Links and further reading:

The World’s Greatest Unsolved Mysteries – Lionel and Patricia Fanthorpe

Norfolk Folklore – Hugh Lupton

Norfolk Heritage Explorer

Eafa short film

The multilingual folk tale database

Photographs © Nick Stone 2017.

Illustration Randolph Caldicott 1879.

Prints available from this series here.

Wonderful. Thanks.

Beautifully spellbinding thank you.

Thank you, fascinating research and air of mystery.

Reading this on a quiet Sunday evening in California was the break I needed from the madness of 2020. Thank you.