Like badgers in channels of hypocausts devoid of fire, The Mouldwarps scatter the cairns of our mothers, And the bogs hold our fathers pinned to wicker.[1]

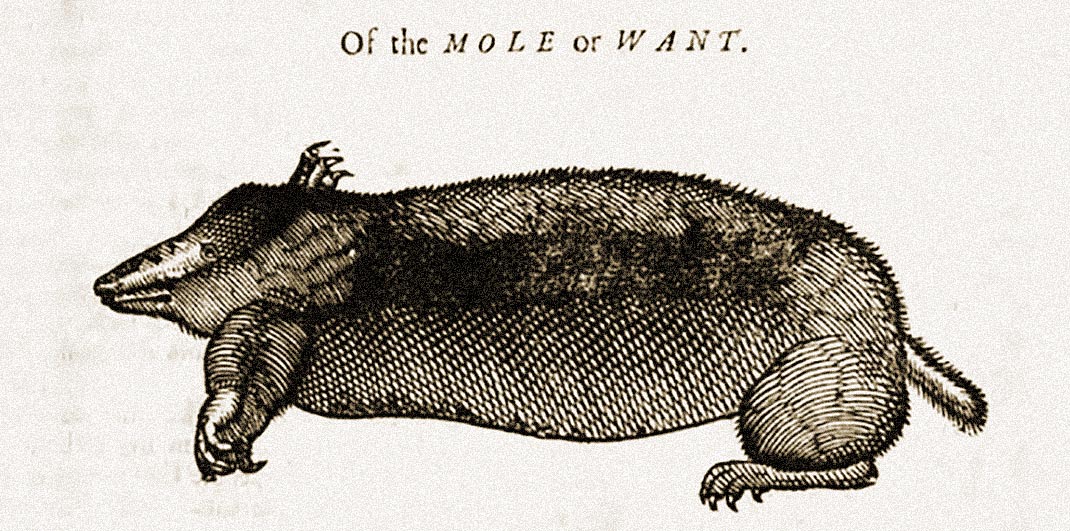

The mole is an ‘earth-thrower’ – a mouldywarp, molywarppe, moudiwarp, mouldwarp, moldwarp. The collision between the mole and folklore has often been to the detriment of the mole. In lore a severed paw of the mole, if worn in a bag around the neck could cure toothache and scrofula – the ‘King’s Evil’. Moles won’t touch earth stained by blood, if moles dig deep a dark winter is coming, moles are blind. The blind or hardly-seeing mole is a recurrent motif in folklore and literature but although the mole does have anatomical regression of its eyes due to its burrowing below ground they can see. Their lives are about the conquest and consumption of earthworms in the dark.

But the mouldwarp is also a recurrent feature of political prophecies throughout the medieval period and up to our own. Peter Ackroyd has even gone so far as to name our age the ‘Age of Mouldwarp’. It may even be tentatively suggested that the touch of the mole to heal scrofula may itself be about the touch of the Mole King. Generations of sufferers saw their only cure for the ‘Kings Evil’ in the touch of the Kings of England and France.[2] The touch of our subterranean, burrowing king may itself be a refraction of that myth. But the folklore and myths of the moles have had a profound effect on the kings above their realm – the underworld of the moles was itself part of the estate of other kings and for all their burrowings, a decisive part of it. In one specific moment the humble Mole estate was to choose the kings of England’s upper realms. At important moments of crisis and contestation the ‘Mouldwarp prophecies’ would play a central part in the fate of kings.

The moorlands of North East Yorkshire have long been associated with mole folklore – specifically the mouldwarp legends. The mouldwarp in local custom is naturally associated with the realms below the earth and is often linked to the Hobs and the Fairies who leave their mark in the place names of the moor and the dales. They are closely linked with the thousands of cairns and burial mounds across the Danby, Castleton, Great Hograh, Urra moors which are often on the highest or most significant points of the landscape. The mounds were often seen as the entrance to the world below or the houses of the mouldwarps, Hobs and Fairies. Fences below the moor are still today draped with the hunted skins of moles. Like the extinct wolves of the moor there was a bounty on their skins. Yet even though the cairns are associated with the mouldwarp there are only rabbits in the excavated mounds – the soil is too acidic for earthworms and the moles are only to be found deep down in the dales or in the fields on the borders of the limestone ridges of the southern moors towards Helmsley at places such as Mole End in Shallowdale not far from the very Roman camps at Cawthorne that brought the rabbits here.

One of the most distinctive aspects of the folklore of the moorlands is the permeability and porousness between the human and the animal. It is almost as if there is some reliquary memory or archive of hybridity. The ghosts here are far from opaque or fleeting – they are corporeal entities who rise as themselves from their burial places or entwined with beasts. Witches turn into hares and birds, labourers join their hands with Fairies, the Hobs take infant human children for their own or live in the houses of humans as at Hart Hall, Glaisdale. There is an indecision or a confusion here about the markers between the worlds of human and beast, of the above and below worlds. Our beings are collisions, collaborations, coalitions and alliances. Often the human becomes the refuge for other beings seeking sanctuary or darker beings who want to take over our sentience.

Perhaps the most dedicated archivist of the hybrid beings of the moorlands was Canon J.C. Atkinson in his Forty Years in a Moorland Parish. He documented in his own time, the latter half of the nineteenth century, the oral accounts of these entities – the Fairies of Fairy Cross Plain in Fryupdale, the multiple iterations of the Mouldwarps, and the ‘little peoples’ of the ‘houes’ – the wafts, wraiths, beings of the moor.[3] Atkinson talks of what we might call the ‘witch cosmologies’ of the ‘folklore firmament’, as he so describes it, of the North York Moors.[4] As Atkinson says ‘…more than forty years ago, a very noteworthy proportion of these witch stories were not only localised, but the names, the personality, the actual identity of the witches of greatest repute or notoriety were precisely specified and detailed’.[5] This is disingenuous in the sense that Atkinson knew exactly the ‘specific abodes’ of the witches, and not only this – he knew what he calls their ‘quasi-forms’ – the witch/hare hybrids who were often the focus of pursuit by local labourers.[6] Not only would the witches and the mouldwarps transform their beings – the bee populations of the moors, often from the bee-boles of Danby head and Westerdale would themselves be sentient – often the role of the beekeeper would be to possess the hearts of the bees and imbue them with human sentience.[7] Much of this was linked to the Odin cults of the moors and to the goddess Freya and the importation of Norse conceptions of corporeal ghosts and entities. But for Atkinson this was profoundly related to what Tom Scott Burns has called his ‘love of the buried centuries’.[8] Atkinson’s own cosmology and understanding was related to his excavations of hundreds of the burial mounds of his moorland locality. He literally paced out the routes of witches and mapped the lairs of mouldwarps in the fields and moors around the vicarage. He made no distinction between converse with witch or Quaker. Witches like ‘Auld Nanny’ or Betty Strother or Nanny Pierson were part of the world of both animals and the dead. In what Marion Atkinson calls ‘an area of ancient memories’ the fairies were the spirits of the dead and of the dead worlds below the cairns.[9]

But the local folklore of the Mouldwarp, linked as it was to both witches and prophecy, would move beyond these moors and dales to affect the course of the realm above – leading many of the proponents of the prophecy themselves to the lands of the dead. The so-called Mouldwarp prophecies recurred time and time again (in their extant forms without an original source) in the medieval period as part of the Book of Merlin. They were used as coded assaults on kingship and certain specific kings like Henry IV but found their epitome during the Pilgrimage of Grace and the northern rebellion against Henry VIII. As A.G. Dickens has said – the Pilgrimage ‘was riddled with rumour, fable, folklore and prophecy, particularly by those prophecies concerning the rise and fall of kings which are traceable to the writings of Geoffrey of Monmouth and which had appeared in former occasions, for example in the days of Hotspur and Henry IV’.[10] The predominantly Catholic uprising used the Mouldwarp prophecies as its ideological ballast in its contest with Henry but the Mouldwarp motifs had previously been used by the Lollards and early protestant reformers. Using these coded messages, often related to the landscapes in which they lived, the subversives would come to understand themselves and their futures in terms of prophecy – as Dickens has said – ‘long experience had made the Lollards adepts in the art of concealment’.[11] He argues that mid-Tudor heresy – ‘often fragmentary, fleeting, and elusive’.[12]

Not only did the Mouldwarp prophecies ask who was to be the Mole King, they were profoundly rooted in the landscape in which the Pilgrimage predominantly emerged – the North York Moors and to some extent the dales to the west, and wolds to the south of the moors. Rupert Taylor long ago referred to the Mouldwarp prophecies as Galfridian – the interaction between humans and animals in which animals stand in for humans and vice versa. Capons, Cocks, and Moles were not part of any kind of abstract symbolism but were often codes for real human beings, their physical and mental characteristics, or their names or birthplace.[13] It is not the place here to retell the flight and journey of Sir Francis Bigod across the North York Moors, the German ocean, and finally to his impaled head in Henrician London but Bigod and his friends were enwrapped in the Mouldwarp prophecy. Bigod was born at ‘Seton How’, now known as Seaton Hall, in 1507, above Staithes and over Roxby moor from Canon Atkinson’s later parlour in Danby vicarage. Bigod’s lands enclosed the cairns of the moor and the fields of the moles. His father may have been killed fighting the Scots at Flodden moor. 25 Stanzas of ‘The Fall and Evill Success of Rebellion’ written by Wilfrid Holme in 1537, were dedicated to Bigod and his role in the rebellion. This reworking of the Mouldwarp myth implicates both the Percy and Lumley family, long associated with the Mouldwarp prophecy, and Robert Aske, leader of the pilgrimage and collaborator with Bigod. In the final sections the Mouldwarp becomes king of the land. This is the vision of Aske and the Mouldwarp king;

Foorth shall come a worme, an Aske with one eye,

He shall be the chiefe of the meinye

He shall gather of chivalrie a full faire flocke,

Half capon and halfe cocke

The chicken shall the capon slay,

And after that shall be no May.[14]

We know from accounts of interrogation that Aske of Swaledale was one-eyed and that the cock was the motif of his allies the Lumleys. The multiplication of entities and their metamorphosis as worm, cock, capon, mole is as present here as in the lore of the moor. The rebel multitude largely emerged from the estates of the rebel families – of Bigod, Aske and Lumley but also from the monastic estates of the moors such as the Carthusian priory at Mount Grace and of Guisborough – themselves built in the desolate moors and dales of the north. Out of all of the lore and the fables of the pilgrimage ‘Most potent of all was the Mouldwarp prophecy, which had first been heard of in the fourteenth century, had surfaced again in the time of Henry IV and now reappeared in all its rambling strangeness’.[15] John Dobson, vicar of Muston, south of the moors in the wolds would be executed in 1538 for his part in the pilgrimage but as Geoffrey Moorhouse makes clear – ‘what cost him his life was his habit of making subversive predictions, including a version of that old standby the Mouldwarp prophecy, and one in which he foretold that the Lumleys would unseat Henry from his throne’.[16] Other repetitions of Mouldwarp appear in the testimony of William Todd, prior of Malton on the south side of the moor.

The quasi-forms of the Mouldwarp reflect the shifting patterns in human sentience and self-elaboration itself. Unsure what humans actually were and enmeshed in the imaginaries of mythical beasts the multiple combinations of beings were part and parcel of the human world as well as the interventions in that world from the land of the dead. The identification of the Mole King, of the usurpers, of the animals that entwined themselves with humans would lead many people of the moorlands to their deaths. It may be that the touch of the mole for scrofula was the gesture of a king. Canon Atkinson found few remnants of kings in the excavation of the Hob’s empire at Hob Cross and Hob-on-the-Hill. The rumours of treasure were unfounded unless one thought that broken beakers were treasure enough. It is only in recent years that a princess from the time of that mythical Merlin was unearthed in all of her grandeur from the cliffs above Seaton Hall, home of Sir Francis, long a place of burial and disarticulation going back into the ‘buried centuries’. Ironic them that this was in a field full of moles and not in the stone bowers of the sandstone heights where no mouldwarps would go. There are earthworms enough in the bed of princesses.

Guest post: Martyn Hudson

References

J.C. Atkinson (1891/1987) Forty Years in a Moorland Parish: Reminiscences and Researches in Danby in Cleveland, Leeds:M.T.D. Rigg.

Marion Atkinson (1981) Legends of the North York Moors: Traditions, Beliefs, Folklore, Customs, Lancaster:Dalesman.

Tom Scott Burns (1986) Canon Atkinson and his Country, Leeds:M.T.D. Rigg.

A.G. Dickens (1967) The English Reformation, London:Fontana.

A.G. Dickens (1982) Lollards and Protestants in the Diocese of York, 1509-1558, London:Hambledon Press.

Martyn Hudson (2006) ‘Parish of our nativities’, in Alan Whitworth(ed.) Aspects of Whitby, Whitby:Culva House press, 30.

Geoffrey Moorhouse (2002) The Pilgrimage of Grace: The rebellion that shook Henry VIII’s throne, London:Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Rupert Taylor (1911) The Political Prophecy in England, New York:Columbia University Press.

[1] Martyn Hudson (2006) ‘Parish of our nativities’, in Alan Whitworth(ed.) Aspects of Whitby, Whitby:Culva House press, 30.

[2] Marc Bloch (1973) The Royal Touch: Sacred Monarchy and Scrofula in England and France, trans. J.E. Anderson, London:Routledge.

[3] J.C. Atkinson (1891/1987) Forty Years in a Moorland Parish: Reminiscences and Researches in Danby in Cleveland, Leeds:M.T.D. Rigg, 52-59.

[4] Ibid, 73.

[5] Ibid, 81.

[6] Ibid, 81-87.

[7] Ibid, 239.

[8] Tom Scott Burns (1986) Canon Atkinson and his Country, Leeds:M.T.D. Rigg.

[9] Marion Atkinson (1981) Legends of the North York Moors: Traditions, Beliefs, Folklore, Customs, Lancaster:Dalesman, 5.

[10] A.G. Dickens (1967) The English Reformation, London:Fontana, 180.

[11] A.G. Dickens (1982) Lollards and Protestants in the Diocese of York, 1509-1558, London:Hambledon Press, 10.

[12] Ibid, 243.

[13] Rupert Taylor (1911) The Political Prophecy in England, New York:Columbia University Press.

[14] A.G. Dickens (1982) Lollards and Protestants in the Diocese of York, 1509-1558, London:Hambledon Press, 128.

[15] Geoffrey Moorhouse (2002) The Pilgrimage of Grace: The rebellion that shook Henry VIII’s throne, London:Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 40.

[16] Ibid, 347.

Image: Edward Topsell. The History of Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents, published in 1658.

Fabulously wide-ranging piece. I would love to be able to print this off.

May I quote you in a piece I’m writing about Richard II and his nemesis?

Hello. Yes, I’m sure if you just credit Dr Martin Hudson-Watts, and provide a link where possible that would be okay.