There’s a focus, out there. You’ll see it in most cemeteries on the old front. The famous dead, the men, and boys who achieve some infamy by dint of their bravery, age or circumstances. Sometimes it’s a footballer who scored big in 1912 before signing away four years, sons of authors, prime ministers or poets. It may be the medals pinned on for the acts that verge on near lunacy or the quiet treading of mud through a rain of shattered cast iron and hollow lead to pick up the wounded or the dying.

They sprout a forest of poppies around their graves, but with the exception of the remembrance circuit, smaller cemeteries are generally quite quiet places. But there is still this hushed chatter, the static of the markers with the names, the places and the messages each one telling a story of who lies below. The dating of graves and position can show more detail if you have even a vague idea about the flow of the war. Even the unknown sometimes tell something, the remnant of a cap badge on a body allowing some sense of person via a regiment.

Often a small amount of digital digging can show still more reveal the cold blue shape below the surface, underneath these white tips in this ocean of manicured green. A name can lead to a place, that leads to a family; wives, parents and children, the looping backward branching across a city, counties, countries and continents. Sometimes a census will place tools in their civilian hands; bricklayers, drivers, office boys and old soldiers lie next to bakers and railway workers lining these whispering streets like neighbours smoking on doorsteps.

The focus is on the most painful, the most moving. The very young who shouldn’t have gone, boys doing men’s bidding. And the old, those who despite having a get out of jail free card, went to desperate measures to go and do their bit whatever that bit was supposed to be. Then there’s those who were shot at dawn, up there with the saddest of sights of all is a man who was tied to a post and executed for not being adequately equipped to work out whether flight was better or worse than fight. A fear of dying leading to the sharp retort of death the ignominy of being desptached by your own side, poor bastards scattered across the old lines like chaff, from tiny outliers behind the lines in hidden corners of commune cemeteries, to massed ranks of those despatched by firing squad at Poperinghe, buried on together on the edge of town.

Dartmoor Cemetery is almost lost because of where it is, yet it actually sits just off a main road on a side road that you take to get to the Norfolk Cemetery at Becourt. I’ve passed it repeatedly on trips and never stopped for some reason. It’s not unlike the Norfolk Cemetery where I always head early on to stare at the familiar Norfolk names; the Claxtons, Hewitts and Ponds. Dartmoor too has grown long against the road, stretched out beside the tarmac in the shelter of two low ridges, limited and protected by the geography, it’s name remembers another location, something it gained from the early inhabitants the Devonshires and their homesickness in 1916 they cluster together where these burial ground first grow in these villages of echoes, .

There are some famous graves in here: A Victoria Cross. Medals and bravery are always a good casual starting point. He’s James Miller, a man who ran back and forth between the lines with a message and a hole right through him, then died on his return having done the job. It also contains the oldest known combatant on the front; Henry Webber aged 68. There’s a deserter too, John Joseph Sweeney one of the Shot at dawn. Who ran away at Armentieres, and who can blame him. It’s difficult to not pat him on the cold stone shoulder for what it’s worth. I rather think I might do the same. He came from New Zealand for what, this? Our modern liberal outlook it’s so much easier to understand their fear, the mental health issue of PTSD and conflict. When I’m back then in my head I’ve occasionally thought I would myself have run from this nasty little game of luck, take a chance in a barn in a stolen farmers shirt. All the pain and death, the ghastly Hun across the way, ‘Leute wie uns wirklich’.

I end up staring at Lall-Din, his name wrapped in Script, a muslim mule driver with the ammunition columns of the RHA, he died on the 1st of September, there is no information at all, he is all but lost.

The thing that drew me to Dartmoor was trying to understand. To draw a picture out of the worn and pixelated remains of their lives. Two men in particular. I am a father, I have children. I understand that thing, that deep genetic route of survival, the way most people would put their lives on the line to enable that connection and division to continue. There are men in here I want to meet, they both have the surname Lee. I looked them up before I crossed the channel. The internet repeatedly says ‘Look at these two, shocking isn’t it’. It’s hard to disagree, but it adds no flesh to the bones. There’s this vague hope when you stare at these things you might glimpse beyond that time-blurred scribbles on faded and sometimes burnt forms.

It is so easy to dispense our grief in measured doses like a drug. Hammer in another cross for remembrance’s sake. Commemorate but don’t understand, don’t think or lift the corners and look beneath the Great War memes. And not actually look, just feel. So I tried to look harder.

They are rather horrifyingly a father and son. Forty-four years old and nineteen. They lie next to each other over near the layers of small romanesque bricks in back wall. Their graves are tight together with two others who died in the same incident either side. Cars pass blindly behind them rising out of the valley. There are two dogs watching me, roaming in a garden pacing between bee hives, One is a flop-eared hunting hound his low reports ripping at me over a thick hedge from their position on the roof of a shed. They set off a chain of ever distant dogs across the valley, silencing the whisper of the stones. I kneel out of sight in front of George and Robert and they cease for a time.

This is pretty bleak. George Lee and his son died on the same day; 5th September 1916, there is no comfort in the scant official lines that they died together. Nor that they died with other men in the same incident, it makes it worse. These two were presumably part of the same gun team, father and son. And I think that’s the bit that gets me, gets everyone. I assume he was here because his son was here. He went when he didn’t have to because of his age, to keep an eye on his 19 year old. Back home Frances, wife and mother waited, as wretched in hope as the rest of the drawn out lines of Mother’s, fathers and wives waiting to find out, not knowing from one day to the next. What she must have felt when the telegrams came I don’t know, not one but two, just like that.

The records are scant, confusing. 156th Brigade Artillery reports 4 deaths that day near Montauban, I assume it must be them. Maybe a shell struck a gun limber, perhaps they were sitting eating, having a cup of tea, maybe firing the gun, lobbing spinning metal across the countryside. There is no detail. The War diary for the division merely lists them like part of two braces of pheasants, not even names, just fodder, bone meal. There are details if you dig within the pen-strokes. They had Robert in their 20s, he was as far as I can tell an only child. George may have run a pub in Deptford for a time. They lived in Peckham, London. A twitter friend David Underdown who works at the National Archive tells me he has a memory of studying these two. They were seconded to another Division, Robert was buried in a trench by earth thrown up by a salvo, his father and the other men died as they were digging them out when a second salvo roared in. A memory of a memory of a memory of the two men.

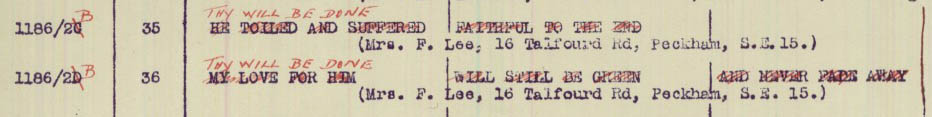

The whispering goes on. At the base of both stones is says ‘Thy will be done’ and whispers something else, so nearly lost.

He toiled and suffered faithful to the end.

Name: George Lee.

Rank: Serjeant

Regiment/Service: Royal Field Artillery

Unit Text: “A” Bty. 156th Bde.

Age: 44

Date of Death: 05/09/1916

Service No: 6029

Additional information: Husband of Frances Lee, of 16, Talfourd Rd., Peckham Rd., London. His son, Cpl. Robert Frederick, also died on service in the same incident and is buried alongside.

Casualty Type: Commonwealth War Dead

Grave/Memorial Reference: I. A. 35.

Dartmoor Cemetery, Becordel-Becourt

My love for him will still be green and never fade away.

Name: Robert Frederick Lee.

Rank: Corporal

Regiment/Service: Royal Field Artillery

Unit Text: “A” Bty. 156th Bde.

Age: 19

Date of Death: 05/09/1916

Service No: 71939

Additional information: Son of Serjt. and Frances Lee, of 16, Talfourd Rd., Peckham Rd., London. His father, Serjt. George Lee, also died on service in the same incident and is buried alongside.

Casualty Type: Commonwealth War Dead

Grave/Memorial Reference: I. A. 36.

Dartmoor Cemetery, Becordel-Becourt

Great work Nick. A really moving account.

Nick,

I’ve gone through my notes, and unfortunately I must just have looked at the various war diaries while at work, and don’t have copies on my PC, so I will have to retrace my steps to remind myself which division 156 Brigade were supporting at the time. I think the respective CRA (Commander, Royal Artillery) diaries were the key. As I said on twitter I don’t think I’ll have chance to do that for a couple of weeks.

Thanks Justin.

David, no rush at all. I think it’s enough for this piece, might be quite nice to do a response piece just on that story maybe? I’ll happily link, or even put it on as an addenda. Thank you for what you tweeted last night.

Excellent article… thanks.

Great article nick, beautifully written such a moving story, thanks for sharing

Hi Nick, I stumbled across your blog while searching for inspiration for an album I’m writing about Fen myths and legends. I really enjoyed what you wrote about the various ‘Black Shuck’ legends, and then came across this bit on Dartmoor cemetery. This interests me as I’m a history teacher and have taken many tours of kids to this cemetery in the past and have never seen anyone else visit. I always point out the father and son grave, but the heartbreaker for me is the grave of E L Townsend as I have his final letter, which I read out over his grave while trying to avoid crying..

I really enjoyed reading your work, and seeing your photography, as I dabble a bit myself.