I thought it was about time I did a bit of quantifying, I’ve done a something in a previous piece here, which scratches at the back of a story but only tells the penultimate episode of it not the rest, there’s other bits clanging and banging about on the internet that I’ve written about it too. So having done a piece on it at the request of for Stephen Bevan at The Cambridge News and because I’m actually quite lazy and it’s half done already so I only have to stick some lipstick on it and slap its bottom. But it’s not that easy, because it isn’t. That. Easy.  I am a trench fever sufferer, not someone who memorises every unit in an attack or every battalion in a division, I am bit of a Great War obsessive. It is a daily thing it ebbs and flows and it has done for almost as long as I can remember. The reason is my Grandfather who I never met, my mum barely knew him either as she wasn’t quite three when he died. She had a the vaguest of memories of big man singing to her while she sat on his knee, she was barely a toddler, a memory that could be just wistfulness willing him to exist, we will never know, she unwittingly passed that need on to me.

I am a trench fever sufferer, not someone who memorises every unit in an attack or every battalion in a division, I am bit of a Great War obsessive. It is a daily thing it ebbs and flows and it has done for almost as long as I can remember. The reason is my Grandfather who I never met, my mum barely knew him either as she wasn’t quite three when he died. She had a the vaguest of memories of big man singing to her while she sat on his knee, she was barely a toddler, a memory that could be just wistfulness willing him to exist, we will never know, she unwittingly passed that need on to me.

When I was a small boy we had lots of tins with things in, old tobacco tins full of panel pins and washers, sweet tins with plasters in, and in an old cold room that smelt of cheese and pickle we had a blue rectangular sweet tin which had a wad of paper in it, some old nursing certificates, a blue bank bag of pre-decimal pennies, sixpences and so on, An envelope of letters and postcards made of lace and three rolled up scrolls; one a warrant my dad received in the RAF, a midwifery certificate of my mums and a parchment scroll. There was also a Dead Man’s Penny and eight medals, four of my dad’s from the Second World War which were wrapped in an old handkerchief and four date from the Great War, two pairs of Victory and British medals. These belonged to my Nan Jesse’s two husbands; my mum’s father and my mum’s step-father; Percy James Parr and Alfred John Ireton.

Birthdays for kids are pretty magical things, the innocently selfish excitement of presents, sweets, games and your friends round for tea. I had an addition to that pattern, because my birthday is Armistice Day, not Remembrance Day, the old name for it. So I had poppies too, and this tin. Throughout my childhood at some quiet moment on my birthday this pale blue tin would emerge from behind the door in the room where it lived with a treadle singer sewing machine, boxes of slides, piles of pickle jars and odd cups and saucers. Dutifully it would be opened and a story would unfold of how Percy had died, actually vanished near Hill 60 in June 1917, and how Alf had met my widowed Grandmother and married her and become my mum’s new dad, and he’d treated her well and was like a father to her, but wasn’t her father really, but he was a good man and honest man who worked in the woods and fields in Cambridgeshire; a forester, a ditch digger. She also said Alf would never entertain the idea of taking a a framed photograph of Percy down from the hallway at their house in Cowper Road “because he deserved to be remembered”.

Birthdays for kids are pretty magical things, the innocently selfish excitement of presents, sweets, games and your friends round for tea. I had an addition to that pattern, because my birthday is Armistice Day, not Remembrance Day, the old name for it. So I had poppies too, and this tin. Throughout my childhood at some quiet moment on my birthday this pale blue tin would emerge from behind the door in the room where it lived with a treadle singer sewing machine, boxes of slides, piles of pickle jars and odd cups and saucers. Dutifully it would be opened and a story would unfold of how Percy had died, actually vanished near Hill 60 in June 1917, and how Alf had met my widowed Grandmother and married her and become my mum’s new dad, and he’d treated her well and was like a father to her, but wasn’t her father really, but he was a good man and honest man who worked in the woods and fields in Cambridgeshire; a forester, a ditch digger. She also said Alf would never entertain the idea of taking a a framed photograph of Percy down from the hallway at their house in Cowper Road “because he deserved to be remembered”.

She had one real brother Tom, and two half brothers Alf and Arthur. We’d pass these medals round, the uncomfortable weight of the Dead Man’s Penny in your hand, unroll the scroll and look at it, then it would all go back in the tin and be put away in the cold storeroom for another year, my head would always fill with images of Hill 60, tales of daring, rolls of wire, explosions of earth and smoke the sound of shellfire overhead, the staccato crack of rifles and the stutter of machine guns all borrowed in my head rolling on a loop from countless wet Sunday war films. As I grew older, I’d sneak into the cupboard and turn the giant penny in my hand and turn and look at the ribbons and medals, reading the edges; Name, Rank, Serial No, Regiment.

Along came the teenage years and in the distance beyond Punk and new wave, crafty fags and hanging about on street corners, the guns still boomed restlessly and Percy looked on from a photo in a little gilt frame on the fireplace, further away but still there.History lessons at school were Abu Simbel and lists of kings I really didn’t, and still don’t particularly have any interest in, while in English covered Wilfred Owen, read and performed Sheriff’s Journeys End over several weeks in a dusty classroom. In my twenties I realised I needed to find out more about this man on the plaque, so the research began. Pre-internet 1990s research involved writing letters on paper with a pen, so I did, Firstly the British Legion, who gave me a few pointers, then the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, who told me where he was remembered, and then the Regimental Museum of The Royal Fusiliers, who sent me a brilliant letter with an annotated photocopy of the extract from the war diary for the week leading up to his very sudden death. It felt like a full stop, reading the facts that surrounded this, the 14 other nameless ‘O.R.’ indistinguishable in the extinguishment suddenly gave me a feel for what it was like in a way nothing I’d read before did, it was just facts but there was a face in it I knew. Next I wrote to the Western Front Association, again very friendly reply, photocopy of map section with trenches and an explanation, some lines and dots and those strange placenames, names again that I knew I’d visit eventually because I had to.

It never stops, like a drip, sometimes a flow, sometimes a roaring gushing torrent of images. I rarely don’t think about the Great War at least once a day, every day. It builds like a wave into massive breakers and then recedes and leaves me alone for a while as it gathers strength to dash me again to drown in all the thoughts and images and everything I’ve read and looked at and stood on and photographed. It is just there like a hot pulsing red hot piece of shrapnel deep in my mind. A red light that flashes and glows on and on and on. And I know I’ll never know him or any of the others; I’ve since found in my family hiding in records, some lost in the burning, their medals in private collections or lost, Sid at Tyne Cot, Herbert near Arras and I’ll never know the survivors either, Fred gassed at Grafenstafl, Frank in the Navy, Alf in the RAMC, all waving farewell somewhere in the past.

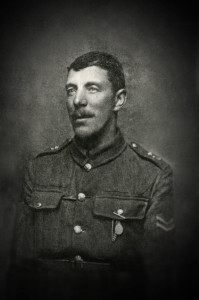

There are some photos in this; The main one of the family together was taken in a studio in Cambridge when my Grandfather was on leave before going back out to the Western Front, specifically Ypres. He died near Hill 60 there on June 7th 1917 the day after the huge mining attack on the Messines Ridge, a huge story in itself, he went over with the second wave on a sunny day, walking past derelict tanks and the ruins of the German strongpoint on Dammestrasse before reaching the German line at the Rosebeke stream, here his company attacked a strongpoint, he was killed along with 13 other ordinary rank and two young officers, he would have been 37. I coveted this photo in it’s cheap frame and it’s now on my wall with his Penny and his medals and Alf’s medals where it should be.

There are some photos in this; The main one of the family together was taken in a studio in Cambridge when my Grandfather was on leave before going back out to the Western Front, specifically Ypres. He died near Hill 60 there on June 7th 1917 the day after the huge mining attack on the Messines Ridge, a huge story in itself, he went over with the second wave on a sunny day, walking past derelict tanks and the ruins of the German strongpoint on Dammestrasse before reaching the German line at the Rosebeke stream, here his company attacked a strongpoint, he was killed along with 13 other ordinary rank and two young officers, he would have been 37. I coveted this photo in it’s cheap frame and it’s now on my wall with his Penny and his medals and Alf’s medals where it should be.

He was a professional soldier, he’d joined the Cambridgeshire Militia as a boy, in 1897 he formally signed up with the Suffolk regiment transferring to the Royal Fusiliers in 1898 he spent his late teens and twenties in Malta, Gibraltar, the Sudan mostly near Khartoum and finally Bermuda returning to Britain in 1905, he married Jesse my Grandmother in 1907 and left the army in 1909 returning to work as a labourer and bricklayer, At some point after the war broke out that is now lost he had come out of the reserve to rejoin the Royal Fusiliers. Family stories indicate he helped train Kitchener’s Army and was at one point at Etaples ‘Bull Ring’.

In the main photo his hand is resting on the shoulder of his son; my uncle Tom who was to die during the Second World War; Tom’s name is on the same memorial in St John the Evangelist, Hills Road, Cambridge and in the round church, he is buried at Mill Road Cemetery. Percy is also remembered along with the other men who died in the same attack on the Menin Gate in Ypres, Panel six to eight. If you are there say hello, he’s up there with most of his mates and the two young officers who died in the same attack, I’ve checked. I suspect secretly hope they may be in Oosttaverne Wood Cemetery, at least some of them, dragged in unidentified after the battle and time had made them unidentifiable. A beautiful well-tended little cemetery as undeserving of my family’s flesh as any I have ever visited. But still. If not he is in the fields still, in that vast cemetery that is the line.

This is the first section of a three part post.

Part 2 of this is here

Part 3 is here.

Thank you for this and your other works on the Great War, and other subjects.