An eye for an eye

Ditchingham sits just North of the Norfolk Suffolk Border. It is to all intents and purposes a suburb of Bungay albeit in a different county and on the other side of a main road. The town and its satellite village sit on the edge of the gentle yawning line that forms the Waveney Valley as it rambles West to East across the countryside to the sea. This is the rift where Shuck has roamed the imagination for centuries, where under nearby Broome Heath our ancestors rest beneath the bracken, and where some of the teeth and bones of mammoths that populate our local museums come from. The area is richly textured with stories, history, and prehistory.

I am not exactly hyper-local despite living in Norfolk nearly all my life. I’d rarely ventured to this bit of the county, coming as I do from North Norfolk which is as good as another country in our slow local dealings. Whenever I do turn up in the area I wonder why I don’t end up here more. I was introduced to these capillaries in the thought map of the locale by two people; Lorna Richardson and Andrew Macdonald both of Waveney Archaeology. They have been involved in the area, know its idiosyncrasies. They know where the past will turn and show its back in the waves of the landscape. It is good to have guides. Andrew, his partner Helen and I went on a quick jaunt to the church.

It is a stunning building, a tall elegant tower with four pinnacles rises out of the trees, it’s visible for miles in nearly every direction. The position is curious, it’s well outside Ditchingham just off the Road between Norwich and Bungay, conspicuous and still somehow hidden. Mostly it is a treasure trove, a spinning wheel of ‘stuff’ turning in front of you. There are indecipherable words and big old ships carved into gravestones in the cemetery. The path outside the door is made of a patchwork of old grave markers complete with inscriptions dating back to the eighteenth century. Table tombs where Sebald stood and pondered, a WW2 VC winner lies alongside local farm workers, their family plots still filling. The Rider-Haggards are present in graves and memorials. Inside the church is clothed in many different fashions. Like most churches it has been dressed and redressed, bits of medieval wood jostle with Victorian Anglo-Catholic paint and glass. It’s big, the tangent light of late afternoon sun warming the plaster and stone dressing. The painted ceiling scintillates. There are layers of history here one over the other over the other, back to the foundations of the chapel, the wood beneath and beyond.

I came here with a explicit task in mind; to visit the Memorial to the Great War. For a church and parish of the size of Ditchingham it is an absolute stunner. A huge black marble and bronze edifice against the entrance wall as you enter the church. It’s an unusual beast too, a monster compared to the taught little wooden frames with hand painted lists of names in most parishes. It is even I n a different league to those isolated crosses and plinths you’ll find in the middle of a village green. This is a serious monument, it fills your mind.

It differs. The backboard of black marble has one obvious peculiarity. It contains a woman, a Staff Nurse, Mary Rodwell. She died on 17th November 1915 almost certainly on board Hospital Ship Anglia. The sunk was sunk by a mine in the English Channel whilst bringing wounded soldiers back from France. This is not unheard of, but It seems unusual, an interloper, an admittance that it’s not a man’s game, that it’s not a game, but here she sits in the usual lists of dead men. I can’t remember ever seeing one before. Perhaps I’m stupid enough to have just never really looked hard enough at those changing times, or I’ve become desensitised to these scrolls of names, man after man after man everywhere you go and look. Maybe most parishes didn’t include them, I actually just don’t know.

The most curious thing is the figure, the sculpture of the soldier. Another rarity; a full sized figure on a memorial for a settlement this size. It’s even more odd because he’s dead. Which was mostly actively discouraged on memorials and at the very least frowned upon. You can’t commemorate with a fact like this, conflicts kill people, we can’t have that. Whilst he hasn’t got the power of Jagger’s giant Artilleryman lying in the rain under a cover at Hyde Park Corner he is still impressive. Finely formed and boned in his unbuttoned coat, hand by his side. He died with his boots on, sacks wrapped and tied around his legs against the splashing mud. For some reason he reminds me of Matthew McConaughey, his face and physique, it jarrs slightly in this context, but it adds a name.

He was sculpted or figured by Francis Derwent Wood. And here is the real story behind this rather striking piece of Bronze. Derwent Wood was reasonably well known, anyone who is vaguely interested in monumental sculpture or in fact just figurative work may have heard the name. He has a fair scattering of public work across Britain and a few worldwide. His best known are probably the Machine Gun Company Memorial or Suicide Club in Hyde Park, the figure of David stands neo-classical honky tonk style between to laurel wreathed Vickers machine guns, David the slayer of Goliath, “Saul has slain his thousands but David his tens of thousands”. As apt as it is inappropriate given the murderous new technology the men were using in this new industrialised mincing machine. His other well known work is Canada’s Golgotha, which given that it shows a crucified soldier nearly caused a diplomatic incident at the time, there are others, plenty of others. Then of course there is Matthew.

He was sculpted or figured by Francis Derwent Wood. And here is the real story behind this rather striking piece of Bronze. Derwent Wood was reasonably well known, anyone who is vaguely interested in monumental sculpture or in fact just figurative work may have heard the name. He has a fair scattering of public work across Britain and a few worldwide. His best known are probably the Machine Gun Company Memorial or Suicide Club in Hyde Park, the figure of David stands neo-classical honky tonk style between to laurel wreathed Vickers machine guns, David the slayer of Goliath, “Saul has slain his thousands but David his tens of thousands”. As apt as it is inappropriate given the murderous new technology the men were using in this new industrialised mincing machine. His other well known work is Canada’s Golgotha, which given that it shows a crucified soldier nearly caused a diplomatic incident at the time, there are others, plenty of others. Then of course there is Matthew.

There’s something special about him and that is where this pulls back round on itself, the snake starts to swallow its tail. Derwent Wood was a trained sculptor, he was apprenticed to a master, Édouard Lantéri. Lantéri schooled a great many monumental figurative sculptors including Jagger, Ledward, and Toft. A sign of the times perhaps, the cream of his classes at what became the RCA memorialising their own dead generation in stone.

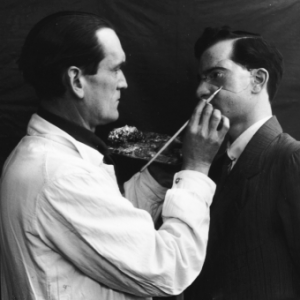

By the time War came Derwent Wood was 41, too old to enlist. He volunteered as an orderly in a hospital, he knew the men in a way that many didn’t and wouldn’t ever. He tended them, these men with flaps or slits instead of eyes, missing jaws, noses torn away. Our intricately boned faces collapse remarkably easily, and here we are with our outward identity removed stoved in by bullets and spinning shrapnel. The visual identity identity and essence of who they themselves were had been reduced to a bubbling mess. They hid in fear of their family and friends shrinking away, the psychological damage and depression of the victims of facial injury is said to be some of the worst, it is part of the collapse of self. Faced by the unfaced he realised something needed to be be done and if anyone had the skills to cover someone and give themselves back what makes them who they are, it is the sculptor, the artist, people like him and Tonks the artist and surgeon.

Tonks recorded the before and after of the damage, his images in oil pastel are both horrific and beautiful in the stark rawness of reality, Almost a precursor to Francis Bacon. In Britain we had nobody like Otto Dix to show the utter barbarity of this oh-so-glorious war, the physical effect on human flesh. No newspapers would carry the truth. His work was consigned to filing cabinets as he catalogued the processes working alongside other proto-plastic surgeons such as Gillies, documenting way as he went. They could work near miracles. Derwent Wood realised that for some the damage was too great to repair, the catastrophic bone loss was impossible for even the most talented surgeon at the time to mend. So he set up a studio in Wandsworth hospital with a cast-maker and three others. They began making tin-plate and copper faces for these men. Each was built on plaster casts of the soldiers faces. Each modelled exactly. Where they existed, pre-injury photographs were used as a guide. Derwent Wood would then hand paint them in-situ on the patient’s face, enamel paints blended to match the complexion of the man adjusting the skin tones to fit exactly. It caught on, other hospitals set up their own Tin nose shops, with around 200,000 men with facial injuries they could only ever help a few but they did, giving them back something that they had lost in the mud, dust, blood and metal of the Western Front. An eye for an eye.

Tonks recorded the before and after of the damage, his images in oil pastel are both horrific and beautiful in the stark rawness of reality, Almost a precursor to Francis Bacon. In Britain we had nobody like Otto Dix to show the utter barbarity of this oh-so-glorious war, the physical effect on human flesh. No newspapers would carry the truth. His work was consigned to filing cabinets as he catalogued the processes working alongside other proto-plastic surgeons such as Gillies, documenting way as he went. They could work near miracles. Derwent Wood realised that for some the damage was too great to repair, the catastrophic bone loss was impossible for even the most talented surgeon at the time to mend. So he set up a studio in Wandsworth hospital with a cast-maker and three others. They began making tin-plate and copper faces for these men. Each was built on plaster casts of the soldiers faces. Each modelled exactly. Where they existed, pre-injury photographs were used as a guide. Derwent Wood would then hand paint them in-situ on the patient’s face, enamel paints blended to match the complexion of the man adjusting the skin tones to fit exactly. It caught on, other hospitals set up their own Tin nose shops, with around 200,000 men with facial injuries they could only ever help a few but they did, giving them back something that they had lost in the mud, dust, blood and metal of the Western Front. An eye for an eye.

Matthew lies here dead. I can never help it with these sculptures, It’s almost a physical necessity to ground yourself on them, to touch the lines where someone fashioned them. He is cold, heavy and dark, he is the dead. The surface marked and oxidised, drips and bat droppings stain the bronze. His nose is strong, cheekbones high, hair ruffled by being in the field. And there on his forehead something I’d never noticed before in photos I’d seen. There is a finger wide gash. It is a shrapnel wound, some glancing blow that has torn the skin, but made not metal into flesh but by flesh into metal, quid quo pro at the hand of Derwent Wood.

I endeavour by means of the skill I happen to possess as a sculptor to make a man’s face as near as possible to what it looked like before he was wounded,” Wood wrote. “My cases are generally extreme cases that plastic surgery has, perforce, had to abandon; but, as in plastic surgery, the psychological effect is the same. The patient acquires his old self-respect, self assurance, self-reliance,…takes once more to a pride in his personal appearance. His presence is no longer a source of melancholy to himself nor of sadness to his relatives and friends.

Francis Derwent Wood, The Lancet, 1917.