Barrack Street is pretty dull inmost respects these days, a humdrum piece of grey carriageway winding through crossings and traffic islands as it links the Magdalen Street flyover to the nexus; Mousehold, Plumstead, Kett’s Heights or along Riverside. It is the epitome of ‘Inner link’ roads, a distillation of how transport can kill a locale. Once this was an area of dense housing; two churches side by side, numerous pubs, an overhang of jettied Tudor leaning into each other and the road, it featured the splendid Pockthorpe brewery building, pubs and shops, and bristled with people, poor people, the people who made the city. The road has forced the houses back into a defensive position behind a berm countering noise but separating the community from the road as banks of step-like flats rise up St James Hill over what was the Cavalry Barracks and later the Horse barracks which leave the remnant of their existence in the name in the road. There are a few more clues to the past; Cavalry Drive and more notably Hassett Close echoing the landscape once occupied by Hassett’s Hall up on the rise in the crook of land almost opposite Cow Tower, beneath which lay the former hamlet which became the city parish of Pockthorpe just outside the city wall. The hall built on the edge of the glacial heath long since gone, demolished for the barracks, the barracks gone for flats, and here we are right now.

Barrack Street is pretty dull inmost respects these days, a humdrum piece of grey carriageway winding through crossings and traffic islands as it links the Magdalen Street flyover to the nexus; Mousehold, Plumstead, Kett’s Heights or along Riverside. It is the epitome of ‘Inner link’ roads, a distillation of how transport can kill a locale. Once this was an area of dense housing; two churches side by side, numerous pubs, an overhang of jettied Tudor leaning into each other and the road, it featured the splendid Pockthorpe brewery building, pubs and shops, and bristled with people, poor people, the people who made the city. The road has forced the houses back into a defensive position behind a berm countering noise but separating the community from the road as banks of step-like flats rise up St James Hill over what was the Cavalry Barracks and later the Horse barracks which leave the remnant of their existence in the name in the road. There are a few more clues to the past; Cavalry Drive and more notably Hassett Close echoing the landscape once occupied by Hassett’s Hall up on the rise in the crook of land almost opposite Cow Tower, beneath which lay the former hamlet which became the city parish of Pockthorpe just outside the city wall. The hall built on the edge of the glacial heath long since gone, demolished for the barracks, the barracks gone for flats, and here we are right now.

The outer curve of the river feeds down meeting Riverside, this is where the river and access road fostered the probably the densest dwellings, built up against the wall on the inside and later outside over the protective wet ditch that drained into the River Wensum where the wall terminates. This riverbank until recently still featured dense housing; arcs of quite attractive brick council flats ran up to the Jarrold Print works, industry hidden behind a metropolitan 1930’s brick frontage, This too has all vanished, a building site, weeds and a car park surrounded by hoardings; a desert created by the faltering tides of capitalism as developers turned there collars up as the profit margins tipped down and return as it tips up again.

It’s a cold day and the light is lowering, the sun just peering over the trees enough to get off a few shots of the rather lovely and reasonably complete corner tower. Despite the plastic surgery it’s had it still looks the part. This is one of the more accessible parts of the wall, sitting as it does just off Barrack Street on the corner of Silver Road. One thing that struck me as I lurked was how little people register it, it’s just another part of our frame of reference; the visible made visually inviable by 800 years of familiarity, just somewhere where dogs piss in the dark, migratory shopping trollies hide in the flora and fauna of cans, tetra packs and crisp bags under a vaulted roof that’s seen more summers than any of us will. It is a really obvious bit of the old that sticks up into the new, and it’s not just a tower, as a rather nice piece of arcading runs up to it and vanishes the other way into a line of flats that terminate. This is where Bull Close fairly recently changed course, turning and cutting through into the city like an invader smashing another hole in the long gone wall in our more recent past. One of the roadside walls has flint in it, I’ve wondered for years as I’ve sat bored in the car at the roundabout if that’s some robbed stone from the thirteenth century, packed and repacked into something else, a wall, becomes a wall, becomes a wall.

The corner tower also has a line of flint that runs down to the road, this marks the line of the wall as it heads off to Pockthorpe Gate or Barre gate as it was also known that sat astride what is now a pedestrian crossing. It reappears on the other side of the road and then disappears under the hoardings into the building site where more remains sit jammed into a weed patch that I clambered through in the heat of the late summer last year on some stupid whim. It a reasonable stretch that’s not immediately obvious and not entirely authentic, heavily rebuilt it also form the wall of an industrial unit, and had had houses nested up to it. None of this is unusual, as a lot of the wall formed bits of other things, Magpie Road in particular until recently had one stretch covered by a pub and one part by a garage that became a printer and was then revealed quite recently. Other long stretches we take for granted on a daily basis formed the back walls of terraces. This part was largely built up to for a lot of its life, slum tenements built right over it up to the river edge tower which I’ll write about at some point, with Water Lane on the outside, basically an open sewer and midden, likely formed from a lost Wensum tributary that was originally filled by a cockey flowing down the hill that’s now Silver Road. It’s long since been infilled. This side has been built up to and not at various points in time. You can, should you fancy a trip through bramble, nettle and wasp-land go and see the remnants, the most obvious of which is a fireplace sitting there exposed on the inner line.*

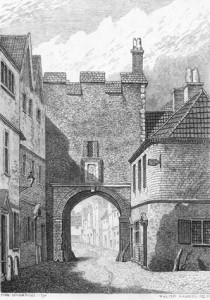

Pockthorpe or Barre gate itself was no real beauty. There is a Pockthorpe brewery advert in existence which I’ve seen in a local pub that shows an illustrator’s imagined view of Pockthorpe Gate with the castle like brewery behind even though it had long gone when it was drawn in the mid-twentieth century, I suspect probably based on an illustrator after Ninham, which was also based on another sketch by John Kirkpatrick. There’s some influence too from other maps that show towers but I don’t have a copy of myself which makes me grind my teeth slightly. But we have Ninham’s drawings and the etchings (right) that follow and that gives a clue to this quite narrow gateway, which says a lot about the demise of all the gates in an expanding city. It had seen some things, partially rebuilt after being badly damaged by Kett’s Men in the dangerous summer days of 1549. in the seventeenth century when Norwich was in the thrall of largely Parliamentary support the gates was ramped with earth to prevent any attack on the Ironsides garrisoned and supplied within. In 1792 it ceased to exist, pulled down, even Ninham himself missed seeing it by two years. Two years or two hundred and twenty-two – there’s not much in it if it’s not there, we’ve all missed out it would seem, next time you drive along Barrack Street, you drive through flint ghosts, there in your imagination if you choose to let them in..

Pockthorpe or Barre gate itself was no real beauty. There is a Pockthorpe brewery advert in existence which I’ve seen in a local pub that shows an illustrator’s imagined view of Pockthorpe Gate with the castle like brewery behind even though it had long gone when it was drawn in the mid-twentieth century, I suspect probably based on an illustrator after Ninham, which was also based on another sketch by John Kirkpatrick. There’s some influence too from other maps that show towers but I don’t have a copy of myself which makes me grind my teeth slightly. But we have Ninham’s drawings and the etchings (right) that follow and that gives a clue to this quite narrow gateway, which says a lot about the demise of all the gates in an expanding city. It had seen some things, partially rebuilt after being badly damaged by Kett’s Men in the dangerous summer days of 1549. in the seventeenth century when Norwich was in the thrall of largely Parliamentary support the gates was ramped with earth to prevent any attack on the Ironsides garrisoned and supplied within. In 1792 it ceased to exist, pulled down, even Ninham himself missed seeing it by two years. Two years or two hundred and twenty-two – there’s not much in it if it’s not there, we’ve all missed out it would seem, next time you drive along Barrack Street, you drive through flint ghosts, there in your imagination if you choose to let them in..

Previously: The walled city part one, and the walled city part two. The City wall map is here.

February 2015

*Addenda; This has all changed since 2015 when this was written, the wall has been stabilised by the developers, which has at least preserved it, it’s now quite accessible again, albeit sanitised and less likely to cause bramble damage.

Possible relative christened 9th August 1584 in St James Pockthorpe- Elizabeth Armes daughter of Henry Armes and Thomas Armes 17th October 1587